A modern robot can stack boxes, pick items from shelves, and navigate corridors, then stall at a closed door. The irony is that doors are among the most “normal” objects in indoor life. They are also a concentrated stress test for robotics: a few seconds of action that require precise perception, contact-rich control, and recovery when things go wrong.

Classic work on autonomous door opening describes the core difficulty bluntly: opening a door with a mobile manipulator involves tight coordination between the base and the arm, making the problem high-dimensional and hard to plan. That complexity becomes sharper with doorknobs, which demand controlled torque while the robot’s sensors are being blinded by its own arm.

What a robot must do to open a “simple” door

For a person, the sequence is automatic. For a robot, it is a pipeline.

First, it must identify the handle, estimate its position and orientation, and approach without colliding. Door handle recognition and localisation using depth cameras is an active research topic precisely because handles vary and can be hard to generalise across.

Second, it must align the wrist and fingers to the handle’s axis. For a round knob, small misalignment means the robot presses into the door skin or applies torque that turns nothing.

Third, it must establish contact and grip. This is where the task stops being a vision problem and becomes a physics problem. Many “versatile” door opening systems explicitly add exploratory contact and force measurement because the robot cannot assume it knows the door’s characteristics in advance.

Finally, it must turn the knob or depress the lever, retract the latch, and push or pull the door while tracking the hinge arc. If it cannot open wide enough, it cannot traverse, which is why planning work focuses on coordinated arm-base motion rather than just knob turning.

The moment vision fails, touch and force control take over

The critical moment is contact. The robot’s hand covers the handle, the camera view degrades, and reflections on metal hardware can confuse depth sensors. A well-known response is to combine modalities: use vision to find the handle, then rely on wrist force-torque sensing and tactile sensors in the gripper to regulate contact and motion.

This is also why door opening is a popular benchmark for tactile learning. Sim-to-real work that models tactile sensors in simulation reports improved real-world door-opening outcomes when tactile feedback is included. The general lesson is straightforward: when you cannot see, you must feel, and you must control forces, not just positions.

How doors defeat robots

Plain-English box: how doors defeat robots

- They hide the important information: the latch state is not visible, and the handle can be occluded.

- They amplify small errors: a few millimetres of misalignment can turn into a jam.

- They change under load: seals, warped frames, and hinge friction shift the required forces.

- They demand torque and grip together: turning a knob needs rotational force while the grasp must not slip.

- They punish rigidity: stiff control drives the hand into the door, compliant control is safer but harder to tune.

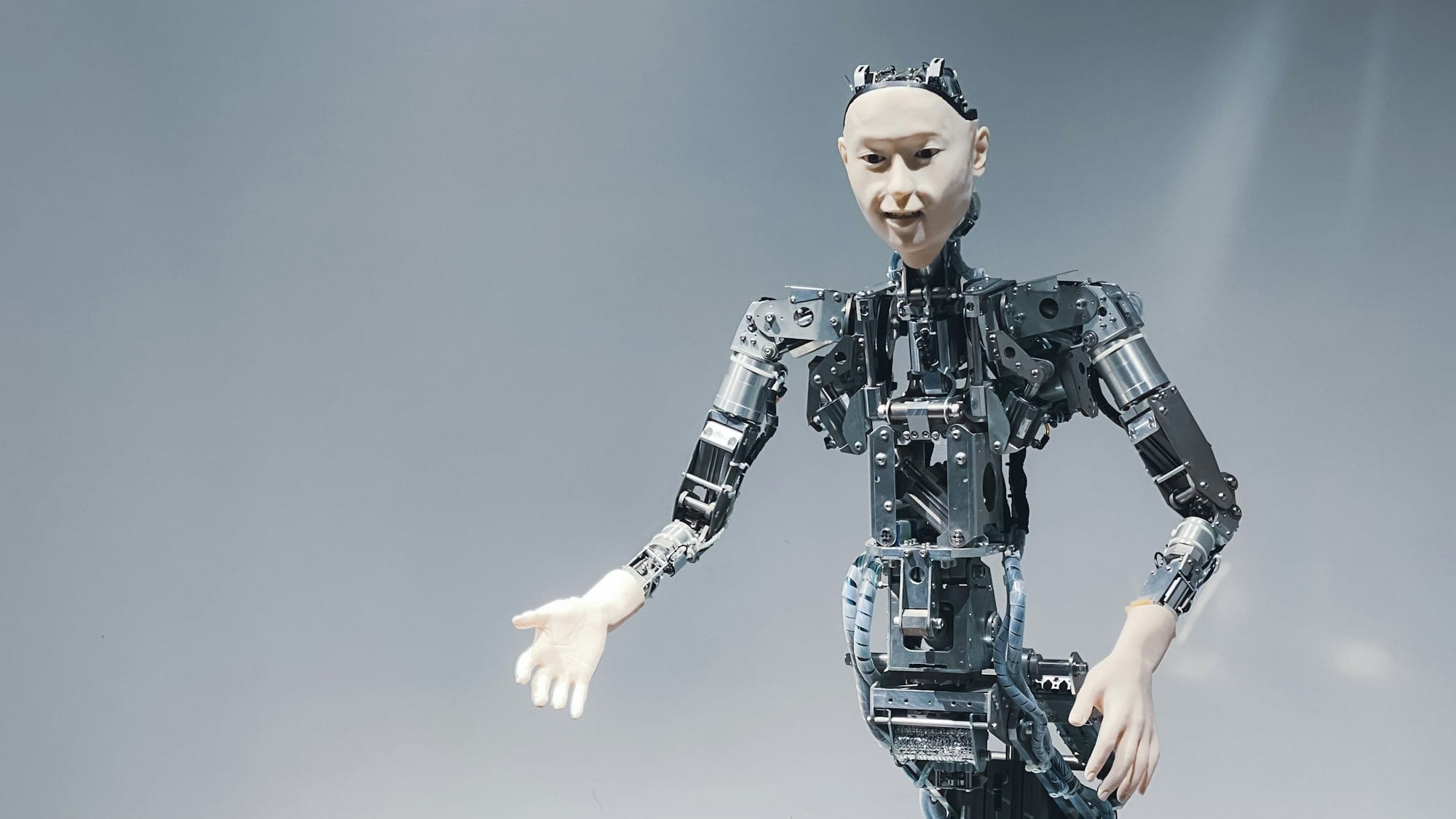

Hands and grippers: why the hardware matters

Robots do not “hate doorknobs” emotionally. They hate the geometry and physics.

A parallel-jaw gripper, the industrial default, is strong and simple, but not naturally suited to round knobs. Reviews of industrial grippers underline how common these two-finger designs are, which is part of the problem in human-built environments.

Suction can be excellent on flat, clean surfaces, and multi-cup designs improve robustness for suitable objects. But doorknobs are often curved and textured, offering little sealing area.

Underactuated hands, designed for passive compliance, can tolerate small pose error and reduce control complexity. They can grasp more “forgivingly”, but high-torque rotation can still expose slip limits.

Anthropomorphic hands match the object design intent, because door hardware is made for human fingers and wrists. Research reviews point out both the promise and the persistent control complexity of five-fingered dexterity in unstructured settings.

Soft grippers add compliance and safety, and soft robotics reviews emphasise compliance as a fundamental advantage. The trade-off is torque transmission and precision, which are exactly what doorknobs demand.

Common failure modes

Common failure modes box

- The robot reaches the handle, then slips during the twist.

- The knob turns, but the latch does not retract due to binding.

- The robot pulls before the latch clears, causing a stall.

- The robot opens the door, then loses the hinge path and collides.

- The controller reacts too stiffly, triggering safety stops.

Door-opening control papers often structure the task into phases and use force feedback to manage unknown constraints, because recovery is where brittle systems fail.

Safety and standards: pinch points in shared spaces

Doors are pinch points. A robot operating around humans must treat contact as a safety-critical event, not simply an error to be ignored.

Industrial robot integration safety is covered by ISO 10218-2, which includes safeguarding considerations across integration and operation. Collaborative industrial settings are addressed by ISO/TS 15066, which supplements ISO 10218 for collaborative operation.

For service robots operating near the public, ISO 13482 sets requirements for personal care robots, including mobile servant robots, and UL 3300 sets safety requirements for service-type robots designed to operate in proximity to consumers. In practical terms, safe door opening requires conservative force limits, reliable detection of unexpected contact, and predictable failure behaviour.

What changed recently: touch, sim-to-real, and generalist manipulation

The trend line is positive, but the wins are specific.

Touch is getting more usable in learning systems. Sim-to-real tactile work shows that adding tactile feedback can improve the outcomes of contact-rich policies transferred from simulation. Force-aware door opening systems are also shifting toward controllers and learning objectives that explicitly reduce excessive forces and smooth motion.

At the same time, foundation models and generalist policies are aiming to reduce brittle, door-specific programming. RT-2 explores vision-language-action transfer from web-scale pretraining, while Octo trains a generalist policy on large, diverse trajectory data. These approaches help with generalisation, but do not remove the need for good force control and recovery in high-torque, contact-rich tasks.

Myths versus reality

Myths versus reality box

- Myth: If a robot can grasp objects, it can open doors.

Reality: Door opening needs torque, hinge tracking, and latch mechanics, not just grasping. - Myth: Better cameras solve it.

Reality: The key moment is occluded contact, where tactile and force sensing dominate. - Myth: A human-like hand guarantees success.

Reality: Anthropomorphic hands increase capability, but also control complexity and failure modes. - Myth: A good demo proves real-world readiness.

Reality: Reliability and recovery across varied doors is the difficult part.

What to watch next

What to watch next box

- Tactile sensing that reliably detects slip onset and contact location under load.

- Controllers that blend compliant motion with torque targets without jamming.

- Generalist manipulation policies that can adapt to new handles with little fine-tuning.

- Safety engineering that treats doors as shared-space hazards, including predictable stop and retreat behaviours.

Fact-check list: claims, sources, confidence

- Door opening for robots typically requires coordinated arm-base motion and is high-dimensional, making it hard to plan. High

- Versatile door opening systems often require handle type and pose estimation and use force measurements during exploratory motion. High

- Multi-sensory door opening approaches combine vision with wrist force-torque sensing and tactile sensing to improve robustness. High

- Tactile feedback in sim-to-real RL has been shown to improve door opening task performance relative to policies without tactile sensing. High

- Door opening can be structured into phases such as reaching, grasping, turning, and pulling, with force-torque feedback used for compliance and constraint handling. High

- Impedance or force-aware control is used in holistic door opening approaches with mobile robots. High

- Door handle recognition and localisation using RGB-D is an active research topic due to handle variability. High

- Parallel two-finger grippers are widely used in industrial settings and are a common end-effector baseline. High

- Underactuated compliant hands can provide robust grasps with lower control complexity through passive compliance. High

- Anthropomorphic five-finger hands target human-like dexterity, but control complexity and robustness in unstructured environments remain open problems. High

- Soft grippers emphasise compliance and adaptability, which can improve safety and contact tolerance. High

- Multi-suction-cup vacuum grippers can improve robustness and efficiency in suitable grasping contexts. High

- ISO 10218-2:2025 covers safety requirements for robot systems and integration, including safeguarding during operation and maintenance. High

- ISO/TS 15066:2016 supplements ISO 10218 for collaborative industrial robot operation and work environment safety requirements. High

- ISO 13482:2014 specifies safety requirements and guidelines for personal care robots, including mobile servant robots. High

- UL 3300 establishes safety requirements for service-type robots designed for use near consumers. High

- RT-2 integrates vision-language pretraining with end-to-end robotic control to boost generalisation. High

- Octo is described as a generalist robot policy trained on 800k trajectories from Open X-Embodiment, intended to support broad manipulation and rapid adaptation. High

Contested or context-dependent points, flagged

- “Doorknobs are harder than levers” is generally true for robots because knobs require sustained torque with tight axis alignment, but difficulty depends on handle design, gripper type, and door condition. Medium