If you are buying or building an artificial intelligence product, the number that will decide whether it survives is not the training budget. It is the ongoing cost of inference, the compute required every time a user asks a question, generates text or triggers an automated workflow. Training can be extraordinarily expensive, but it is a one-off event. Inference is a metered utility. When usage rises, so does the bill, and the bill often rises in ways that are not obvious from a product demo.

This is why the economics of AI look so different from the hype that surrounds new models. A prototype can feel cheap because it serves a handful of prompts. A real service has to answer at peak times, meet latency expectations, cope with long prompts, handle traffic spikes and remain stable when people use it in unpredictable ways. The cost of doing that is shaped as much by product design as by which model you choose.

To understand why inference dominates, it helps to separate two phases that are often blurred in public discussion: training and inference. Training is the process of building a model by adjusting its parameters using large datasets and intensive compute. Inference is what happens afterwards, when the trained model is used to respond to new inputs. Training tends to be optimised for throughput and happens in bursts. Inference has to balance throughput with latency, the time a user waits for a response, and it happens continuously.

Tokens, context and the hidden arithmetic of cost

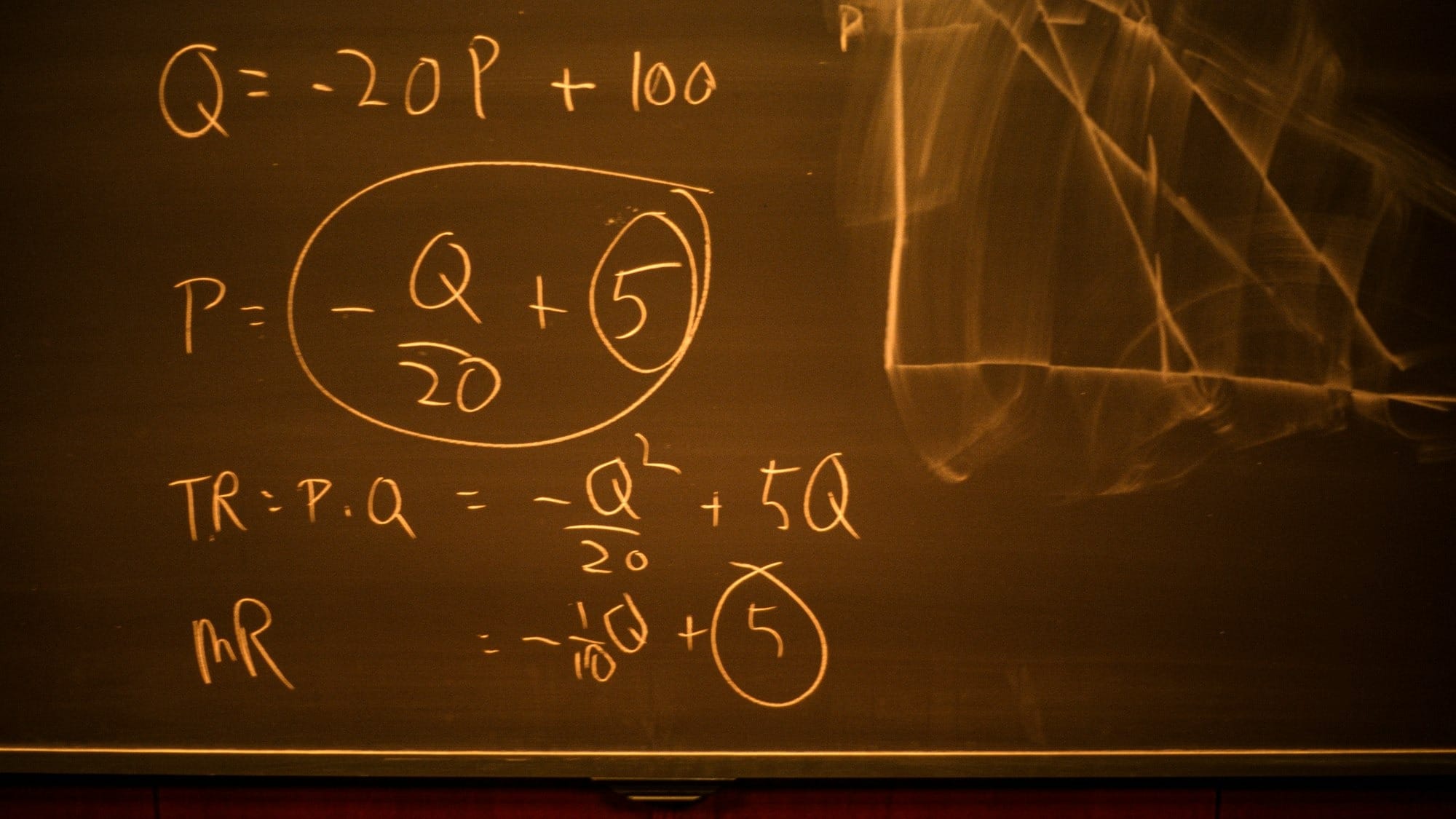

Most commercial AI pricing is expressed in tokens, the units of text that models process as input and produce as output. Tokens are not exactly words, but they are close enough to make budgeting feel straightforward. You send a prompt, you get a response, and you pay for the total number of tokens involved.

That apparent simplicity hides several cost drivers that become decisive at scale. One is that output tokens are usually more expensive than input tokens, and they take longer to generate. Inference is not a single step. A model first processes the prompt and any context, then generates the response token by token. The longer the answer, the more time and compute it consumes. A system that encourages verbose replies therefore costs more and feels slower, even if the per-token price looks modest.

Another driver is the context window, the amount of text a model can consider at once. Large context windows make it possible to analyse long documents, keep extended conversations coherent and perform multi-step reasoning. They also increase the amount of computation and memory required for each request. From a product perspective, a bigger context window looks like a feature upgrade. From an infrastructure perspective, it looks like a rising marginal cost.

Concurrency adds another layer. A model serving one user at a time is cheap. A model serving thousands of users simultaneously must hold multiple contexts in memory and generate responses in parallel. That requires more hardware and tighter capacity planning. If you promise fast responses, you need spare capacity to handle peaks, which means paying for resources that sit idle much of the time.

Latency is a cost problem, not just a user experience issue

In many organisations, inference cost is treated as a simple function of token volume. Token volume matters, but performance targets matter just as much. An interactive system, such as a live chat or search assistant, must respond quickly, which means provisioned capacity to meet demand at its busiest. An asynchronous system, such as overnight document summarisation or batch translation, can tolerate slower responses and therefore run more cheaply.

This distinction is where many AI projects get into trouble. A demo is usually a single call: one prompt, one answer. A real product is a chain of calls. It may retrieve background material, classify the request, rewrite it, generate an answer, check safety rules and post-process the output. Each step can involve another model invocation. Even if each invocation is inexpensive, the stack accumulates cost and latency.

Speed and cost are tightly linked. The time it takes to produce the first token and the time per additional token together determine how many users a system can serve. If a product design pushes models to generate long responses for every interaction, it increases the token bill and reduces throughput, forcing the operator to buy more capacity to maintain responsiveness.

Memory is money

One of the less visible drivers of inference cost is memory. Modern language models rely on storing intermediate information so they do not have to recompute attention over the entire context for every new token. This speeds up generation, but it consumes large amounts of memory. The memory required grows with context length and with the number of concurrent users.

This creates a hard trade-off. Long contexts and high concurrency reduce how many requests a given set of machines can handle. Even if the raw compute power is sufficient, memory becomes the bottleneck. From the buyer’s perspective, this means that generous use of context, such as repeatedly sending full conversation histories or long documents, has a double cost. It increases the number of tokens processed and it reduces overall system capacity.

A plain-English way to estimate inference costs

You do not need a detailed technical model to see how inference costs add up. A rough calculation is often enough. Start with the number of interactions you expect in a month. Multiply that by the average number of tokens processed per interaction, including both input and output. Then apply the provider’s per-token prices, adjusted for whether the work is interactive or can be batched.

The fragile part of this calculation is the “average tokens per interaction”. It includes the user’s input, any retrieved context, system instructions and the model’s response. Small design choices can inflate this number without anyone noticing. Lengthy system prompts, repeated instructions and verbose safety preambles all consume tokens. Over thousands or millions of interactions, they become a major cost driver.

Some models also use internal reasoning steps that consume tokens even if they are not shown to the user. From a billing perspective, those tokens still count. This matters most when high-capability models are used for routine tasks that do not require complex reasoning.

A realistic cost estimate should also include engineering overhead. Inference is only one part of an AI system. There are costs for retrieval databases, vector search, moderation, logging, monitoring and human review. These do not appear in token pricing, but they appear on the balance sheet.

How scale turns small costs into big ones

Consider a publisher that adds an AI feature to summarise articles and answer reader questions. At low volume, the cost feels negligible. As usage grows, the arithmetic changes quickly. Hundreds of thousands of interactions a month, each processing over a thousand tokens, turn into hundreds of millions of tokens. If the feature becomes popular, that figure can jump by an order of magnitude.

At the same time, success creates performance pressure. Users expect fast responses, particularly around breaking news or popular topics. Meeting those expectations may require higher-priority processing or reserved capacity, which raises the unit cost. The result is that growth multiplies costs in several directions at once: more users, more tokens per user, and higher capacity requirements.

Where buyers get caught out

The most common mistake is to budget for typical behaviour and then ship a product that encourages worst-case behaviour. Long conversations, pasted documents and repeated retries all increase token usage. Large context windows make this easier, and therefore more expensive.

Another mistake is to treat all workloads as interactive. Many tasks do not need instant responses. Moving non-urgent work into batch processing can materially reduce costs, because it allows providers to schedule compute more efficiently. Designing products with this distinction in mind is often more important than negotiating a slightly lower per-token price.

A third mistake is defaulting to the largest available model. Bigger models can improve quality, but they also increase cost and latency. Many systems perform better economically by routing requests through smaller models first, using larger models only when the task demands it.

Finally, there is a tendency to focus on headline API prices while ignoring total cost. Even a cheap model can be expensive to operate if it requires extensive engineering, monitoring and compliance work.

How product design shapes the economics

Inference costs are not fixed. They respond to design choices. Caching repeated prompts and instructions can reduce token usage. Retrieving only the most relevant passages rather than sending entire documents into a prompt can cut both cost and latency. Summarising long histories into shorter representations can keep context manageable.

Related reading

- AI translation and speech tools: accuracy, bias, and when to trust them

- AI and misinformation: how falsehoods spread, and what actually reduces harm

- Liquid Reply joins Linux Foundation–backed Agentic AI Foundation

Latency targets also feed back into cost. Faster responses usually mean higher prices and more reserved capacity. Slower, asynchronous processing can unlock significant savings. These are not marginal optimisations. They determine whether an AI feature is a sustainable part of a product or an open-ended liability.

For publishers and content businesses, there is an additional tension. Revenue is often fixed per reader or per page view. Inference costs are variable per interaction. An AI feature that looks like a reader benefit can become a variable-cost engine inside a fixed-income model. That mismatch is why inference economics matter more than demos, and why the next phase of AI products is likely to be defined less by spectacular capabilities and more by disciplined design, tight prompts and a clear understanding of which uses are worth paying for.