Cells have been running a courier network long before humans invented next-day delivery. Every day, they wrap up molecular messages, seal them in tiny lipid envelopes, and dispatch them into blood, saliva and cerebrospinal fluid. These parcels are called extracellular vesicles (EVs) and they are increasingly being studied as both drug delivery vehicles and diagnostic clues.

The pitch is tempting. If EVs already move ribonucleic acid (RNA), proteins and lipids between cells, could they be repurposed to smuggle in a therapeutic message, with fewer side effects than today’s synthetic carriers? Some researchers think so, and the number of registered EV-related clinical studies has grown into the hundreds.

The hard part is turning biology’s messy postal system into something that can be manufactured like a medicine, regulated like a medicine, and trusted like a medicine.

What extracellular vesicles are, and what “exosomes” really means

EVs are membrane-bound particles released by cells. They carry a mix of cargo, including proteins, lipids and nucleic acids, and they can influence recipient cells by delivering that cargo.

You will often see the word exosome used as shorthand for all EVs, but the field has been trying to tidy up its language. The International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV) guidance, known as Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles 2023 (MISEV2023), advises caution about using biogenesis-based terms such as exosomes unless the population has been specifically separated and characterised.

For practical purposes, researchers often talk about subtypes such as:

- Exosomes, typically smaller EVs associated with endosomal pathways.

- Microvesicles, which bud directly from the plasma membrane.

- Other EV subgroups that can overlap in size and content.

MISEV’s core point is simple: EVs are heterogeneous, and methods shape what you think you have.

Interview placeholder: [EV researcher explains EVs as “biological parcels”, and why definitions matter when you are trying to turn them into a regulated product.]

Why they matter, compared with lipid nanoparticles

The benchmark for nucleic-acid delivery today is the lipid nanoparticle (LNP), a synthetic particle built from lipids that can encapsulate RNA and help it enter cells. LNPs proved their clinical value at scale during the COVID-19 messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) vaccine rollout.

LNPs are powerful, but not magical. Reviews note ongoing challenges around toxicity, reactogenicity and immunogenicity, as well as distribution to unintended organs and the need to balance stability with endosomal escape.

EVs are attractive because they are, in theory, nature’s own delivery particles. They may offer:

- Biocompatibility: a membrane composition that cells recognise.

- Potentially lower immune activation, depending on source and purification.

- Intriguing biodistribution: some EVs appear to cross physiological barriers under certain conditions, a focus in neurology-oriented delivery research.

Sceptics reply, fairly, that “natural” does not automatically mean “safe” or “consistent”. EV cargo can vary with cell type, stress, culture conditions and purification method. That variability is precisely why standards such as MISEV exist.

Leading use cases: oncology, neurology, inflammatory disease

EV enthusiasm tends to cluster around three use cases.

Oncology: delivery and diagnostics

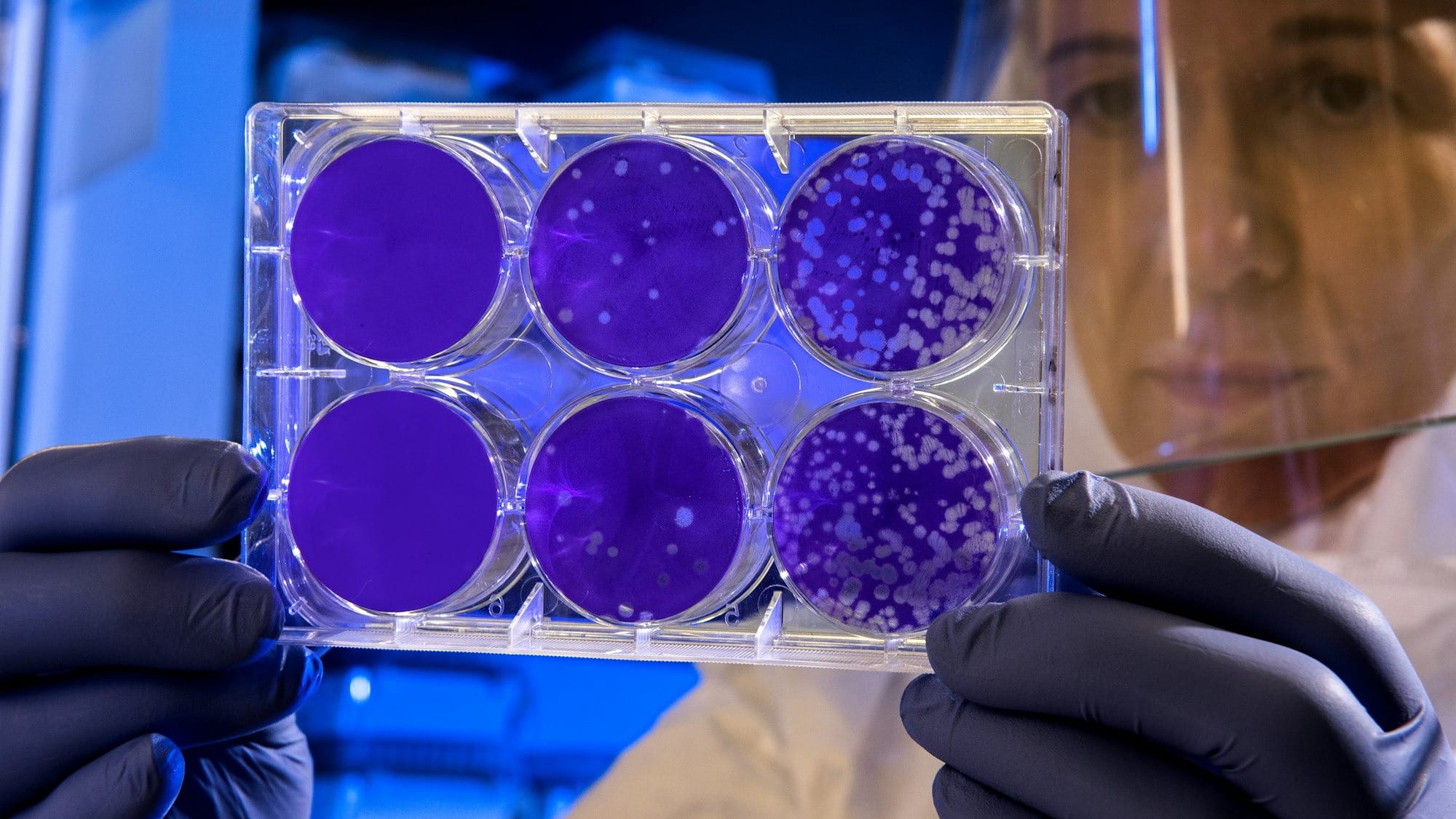

Cancer is both a delivery problem and a measurement problem. Tumours are adept at reshaping their microenvironment, and EVs are part of that communication. EVs in blood can also carry tumour-derived signals, making them candidates for liquid biopsy approaches.

For therapeutics, engineered exosomes are being explored as carriers for small molecules and RNA payloads, with the aim of improving tumour targeting and reducing off-target toxicity.

For diagnostics, the appeal is that EVs can protect fragile nucleic acids and proteins inside a lipid envelope, potentially preserving disease signals in biofluids.

Neurology: reaching the brain

The central nervous system is guarded by the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which blocks many therapies. Reviews discuss EVs as delivery tools for central nervous system conditions, highlighting biocompatibility and the possibility of BBB traversal in some contexts.

This is a high-hype zone, so the reality check is important. “Can cross the BBB” is not a single claim. It depends on EV source, surface markers, route of administration, disease state, and the sensitivity of the tracking method. The field is still arguing about what reaches the brain in therapeutically meaningful quantities.

Inflammatory disease: immune modulation and targeted delivery

Inflammation is where EVs look most like their biological selves. Cells use EVs to signal during immune responses, and stem cell-derived EVs have been studied for their immunomodulatory effects. Reviews cover a wide range of proposed inflammatory and tissue repair applications, while stressing the need for standardisation and robust clinical evidence.

Engineering approaches: loading cargo, surface targeting, designer vesicles

Turning EVs into delivery vehicles is a packaging problem and an addressing problem.

Loading cargo: what goes inside the parcel

Researchers use several strategies, each with trade-offs:

- Passive loading: incubating EVs with a drug in the hope it partitions into the membrane or lumen.

- Electroporation: using an electric field to help nucleic acids enter EVs.

- Producer cell engineering: modifying the parent cells so they package specific RNAs or proteins into EVs during biogenesis.

The catch is that loading can damage vesicles, change size distributions, or introduce contaminants, and methods may not scale cleanly.

Surface targeting: address labels for cells

Targeting aims to alter which cells take up EVs, often by adding ligands, antibodies, or engineered membrane proteins. The goal is to replace blunt biodistribution with something closer to an address label. Reviews describe diverse surface modification strategies, but also note the risk that modifications change uptake pathways in unpredictable ways.

“Designer vesicles”: building the courier you actually want

Some groups aim to design EV-like particles with controlled composition, sitting somewhere between a natural EV and a synthetic nanoparticle. This includes hybrids, membrane-coated particles and engineered EVs. The ambition is consistency without losing the biological advantages that made EVs interesting in the first place.

Interview placeholder: [Manufacturing scientist explains why “designer vesicles” are attractive, and why every engineering tweak creates a new characterisation burden.]

Safety and regulatory questions: what regulators will care about

Regulators do not approve metaphors, they approve products.

Key questions include:

- Identity: what is the product, and how is it defined batch to batch?

- Purity: what contaminants are present, including proteins, nucleic acids, viruses, and process residues?

- Potency: what is the mechanism-linked assay that predicts clinical effect?

- Biodistribution: where does it go, and what off-target effects are plausible?

Reviews of regulatory frameworks for exosome and EV therapies describe active debate about classification and requirements, with a recurring theme: risk-based regulation and a need for rigorous quality attributes in the face of EV heterogeneity.

A parallel issue is the rise of loosely regulated “exosome” products marketed in consumer settings. A Guardian investigation reported UK beauty clinics offering banned treatments derived from human cells, with experts raising concerns about contamination, authenticity and safety. That consumer market is not the same as clinical EV therapeutics, but it shapes public perception and may prompt regulators to draw firmer lines.

Manufacturing and quality control: the unglamorous gatekeeper

If EVs are the cell’s postal service, manufacturing is the sorting office. This is where many programmes stall.

Challenges include:

- Scale: producing enough EVs for consistent dosing.

- Source variability: cell type, culture media, stress, and passage number can alter EV composition.

- Separation and concentration: ultracentrifugation, size-exclusion chromatography, filtration and other methods all bias the final population. MISEV2023 emphasises that method choice affects what you call an EV preparation.

- Release testing: defining specifications for identity, purity, sterility, and potency.

The field is moving towards more industrial thinking. A 2025 paper describes developing a large-scale good manufacturing practice (GMP)-compliant process for an EV-enriched product, including purification, sterilising filtration, and quality control strategies for release testing. Another 2025 review discusses generating current good manufacturing practice (cGMP)-grade EVs using automated bioreactors, pointing to standardisation and scalability as central obstacles.

This is where EVs differ sharply from LNPs. LNP manufacturing is difficult, but it is fundamentally a chemistry and process engineering problem. EV manufacturing is a living system problem, with biology in the loop.

How clinicians might use EVs in five years

If EVs make it into routine practice, the first uses are likely to look practical rather than cinematic.

One plausible near-term clinical pattern is:

- Diagnostics: EV-based assays as add-ons to existing workflows, for example enriching EV subpopulations from blood to improve the signal-to-noise ratio for certain biomarkers, rather than replacing imaging or tissue biopsy.

- Therapeutics: EV-based delivery in niches where current carriers struggle, such as specific inflammatory indications, local delivery contexts, or carefully defined neurology programmes that can demonstrate biodistribution and functional outcomes.

Clinicians will want clear evidence on dosing, durability, adverse events, and comparators. “Better than LNPs” will not be a slogan, it will be a trial endpoint.

Interview placeholder: [Clinician describes what would change their practice: predictable dosing, reproducible manufacturing, and a clear benefit over existing delivery platforms.]

Sceptics’ concerns: what could slow this down

Scepticism in EV science is not cynicism, it is a response to recurring problems.

Common concerns include:

- Heterogeneity: EV preparations are mixed populations, making mechanism and potency hard to pin down.

- Weak comparators: some studies compare engineered EVs to poorly optimised LNPs, or do not benchmark against best-in-class formulations.

- Tracking uncertainty: fluorescent labels can detach or behave oddly, confusing biodistribution claims.

- Potency assays: without a robust potency assay linked to mechanism, scale-up becomes guesswork. Quality and safety discussions highlight the need for clear characterisation and release criteria.

- Regulatory ambiguity: classification differences across jurisdictions can slow global development.

The most grounded EV advocates tend to agree on one point: breakthroughs in manufacturing and standardisation may matter as much as breakthroughs in biology.

What to watch (six to eight milestones)

- Potency assays that regulators accept, linked to a defined mechanism of action, not just uptake.

- Scalable GMP production platforms, including bioreactors and reproducible purification workflows.

- Head-to-head human studies comparing EV delivery with optimised LNP delivery for the same cargo.

- Clear biodistribution data using robust tracing methods, especially for central nervous system delivery.

- Regulatory clarity on classification and minimum quality attributes across major regions.

- Clinically useful EV diagnostics that improve decisions, not just statistical separation of cohorts.

- Reference materials and standard reporting adoption, including wider compliance with MISEV2023-style expectations.

- A credible safety narrative that separates clinical-grade EV medicines from unregulated consumer “exosome” products.

Glossary (six terms)

- Extracellular vesicles (EVs): membrane-bound particles released by cells that carry molecular cargo.

- Exosomes: a subtype of EVs associated with endosomal pathways, though the term should be used cautiously unless specifically characterised.

- Microvesicles: EVs that bud from the plasma membrane.

- Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs): synthetic lipid-based carriers used for delivering nucleic acids such as mRNA.

- Biodistribution: where a therapy travels in the body after administration, including off-target organs.

- Potency assay: a test intended to measure biological activity relevant to the therapy’s mechanism, used to support batch release and comparability.

A grounded view of timelines and limits

EVs are not a guaranteed successor to LNPs. They are a parallel platform with different strengths and different headaches. The field has credible science, growing clinical exploration, and serious investment in manufacturing methods.

The near-term wins are likely to be narrow: defined indications, controlled routes of administration, and products with rigorous characterisation that meet modern expectations for quality and safety. The broader “delivery revolution” depends on whether EV programmes can prove, in humans, that their biological parcels deliver the right cargo to the right address, at scale, with repeatable outcomes.