The problem with giving robots a sense of touch

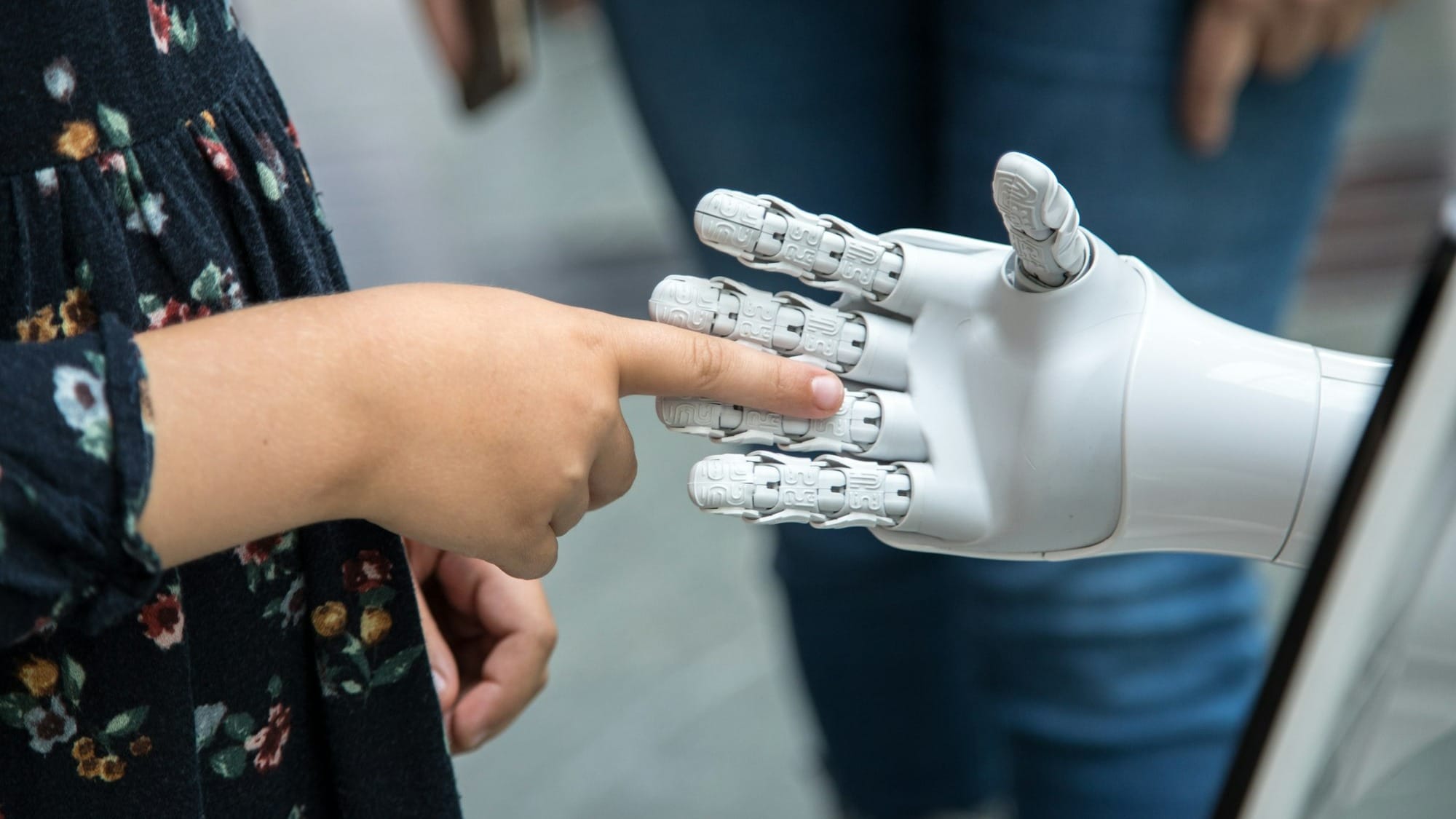

If you want to watch a robot become suddenly, spectacularly useless, hand it something awkward and ask it to hold on.

A vision system can spot an object, estimate its pose and plan a neat approach. Then the fingers close, the object twists a millimetre, and the whole plan collapses into a slow-motion drop. This is why warehouses still struggle with truly general “pick and place” in clutter, and why many robots avoid contact wherever possible.

Touch, in robotics, is often filed under haptics, the broader field that covers sensing and producing tactile sensations. In practice, roboticists usually mean tactile sensing: measuring what happens at the contact patch, including pressure, vibration and the sideways forces that precede slip.

The awkward truth is that touch is not just another input channel. It is a negotiation with the world, conducted at high speed, through squishy materials, under safety limits that do not care how clever your software is.

Why touch is messier than vision

A camera can “see” without changing what it observes. Touch is different: the act of measuring alters the scene. Press harder and you deform the object. Press at an angle and you introduce shear. Move a fraction too fast and friction flips from sticking to sliding.

This is the domain of contact dynamics, the part of physics that covers what happens when bodies meet, push, slide, bounce and grind. Even in simulation, modelling contact and friction reliably is hard, and different numerical methods make different trade-offs.

Then comes the most human of touch skills: catching slip before it becomes obvious. People sense incipient slip through tiny vibrations and small changes in shear force, then adjust grip without thinking. Robotics researchers have spent decades building slip detectors and surveying what works, with the main conclusion being that slip is fast, context-dependent, and not solved by any single sensor.

Timing makes it worse. Touch is usually used inside a feedback loop: sense contact, compute a response, adjust the motion. Delays can destabilise haptic systems and teleoperation, because the controller responds to old information.

And there is a practical wrinkle: tactile sensors live where the damage is. They get scuffed, contaminated, heated, pinched and worn. Flexible “robot skin” arrays face additional challenges around calibration, drift, wiring and turning huge streams of noisy signals into decisions.

Five ways to build a robotic fingertip

Roboticists have not been short of ideas. The trouble is that each comes with its own flavour of compromise.

Capacitive sensors measure changes in capacitance as a surface deforms. They can be made into high-resolution arrays, and reviews put them among the workhorse mechanisms for electronic skin. They can also be finicky in the presence of electromagnetic noise and parasitic effects.

Piezoresistive sensors change resistance when squeezed or stretched, often using conductive composites. They are attractive because the electronics can be simple and low-cost, and reviews highlight their frequency response and ease of use. They can suffer hysteresis and drift, which is a polite way of saying the same touch does not always give the same reading.

Optical tactile sensors are the most literal “robotic touch is vision” approach. A camera watches a deformable, illuminated skin, and software reconstructs what shape is being pressed into it, including lateral motion that hints at shear and slip. GelSight is a prominent example, described as essentially measuring geometry at very high spatial resolution.

TacTip takes a biomimetic route, using soft optical designs fabricated through 3D printing.

DIGIT argues for compactness and cost reduction, because touch does not help if it cannot fit on the finger.

Force-torque sensors typically sit at the robot wrist and measure forces and torques across six axes. They are invaluable for compliance control and “feeling” global contact in tasks like insertion and surface finishing, but they cannot tell you much about what is happening at a specific fingertip patch.

Soft sensors and e-skin aim to cover large areas with compliant sensing, making robots safer and more aware when they bump into things. The best reviews are blunt about the remaining engineering: durability, calibration, system integration, and extracting meaning from distributed signals.

Where touch matters right now

In warehouses, the hard cases are not the obvious ones. It is the crumpled bag, the glossy packet, the item jammed behind another, the thing you can only grab if you feel your way in. Reporting on Amazon’s “Vulcan” frames touch sensing as a route to dealing with cluttered shelves, a task where vision is not enough.

In surgery, the absence of natural haptic feedback has been a long-running complaint, and the research literature keeps testing ways to restore it. A 2023 Scientific Reports review describes evidence that adding haptic feedback can reduce applied forces in studied tasks, though results vary by system and context.

In prosthetics, sensory feedback is tied to control and embodiment. Reviews of sensory feedback for upper-limb prostheses describe efforts to return touch information through non-invasive and invasive techniques.

And in consumer devices, haptics is often about the reverse direction: making people feel clicks and textures that are not there. The same components can blur roles. Research presented at ACM User Interface Software and Technology (UIST) showed how linear resonant actuators, used for phone vibration, can also be used for sensing touch and pressure via back electromotive force.

What changed recently, without the hype

Two shifts are making touch more tractable.

First, the field is building datasets and benchmarks. Tactile perception is moving, slowly, from one-off lab demonstrations towards repeatable comparisons.

Second, tactile simulation is improving. TACTO and related work argue that touch has been unusually difficult to simulate, and propose faster, more flexible rendering of tactile readings to enable large-scale learning and better sim-to-real transfer.

This does not eliminate the physics. It changes the economics of experimentation. You can fail a million times in simulation, then move to hardware with fewer surprises.

The last constraint is safety. If a robot is meant to work near people, touch sensing and control must respect force limits. ISO/TS 15066 codifies collaborative robot safety requirements, and it sits behind many real-world design decisions about how hard robots are allowed to “feel”.

Explainer box: touch terms without the jargon

- Normal force: pushing straight into a surface.

- Shear force: pushing sideways along a surface.

- Slip: motion at the contact patch. “Incipient slip” is the early stage, before the object visibly moves.

- Contact dynamics: the physics of contact, including friction and deformation.

- Sim-to-real gap: what works in simulation failing on real hardware due to mismatched physics and sensor behaviour.

Myths versus reality

- Myth: “Just add a sensor to the finger.”

Reality: Touch is a control loop under latency, noise, wear and safety limits. - Myth: “Optical tactile sensors make touch easy because they look like images.”

Reality: They still rely on elastomer deformation and friction, and produce heavy data streams. - Myth: “If a robot can see a good grasp, it will hold.”

Reality: Studies show touch helps with regrasping and grasp outcome prediction once contact begins.

What to watch next

- Better tactile simulation and contact modelling that captures friction and deformation more reliably.

- Public tactile datasets that make results comparable across labs.

- Lower-cost fingertip sensors that survive real wear and tear.

- Safety-led design as robots move into shared human spaces.

Fact-check list (claims, source, confidence)

- Tactile sensing measures contact-related signals such as geometry, force and slip in robots. Confidence: High

- Touch is “interactive” because measurement requires contact that can change the object state. Confidence: Medium (well supported conceptually; phrasing is interpretive)

- Contact and friction modelling is difficult in robotics simulation and involves trade-offs across methods. Confidence: High

- Slip detection is fast, context-dependent and studied across multiple sensing methods, with strengths and weaknesses. Confidence: High

- Optical tactile sensors infer contact shape from deformation of a soft elastomer viewed by a camera (GelSight). Confidence: High

- Dong et al. demonstrate slip detection using relative motion and shear distortions on the GelSight membrane. Confidence: High

- The TacTip family uses soft optical tactile sensing and 3D-printed morphologies. Confidence: High

- DIGIT is described as a low-cost, compact, high-resolution tactile sensor for in-hand manipulation. Confidence: High

- Force-torque sensors measure forces and torques across six degrees of freedom and are used for force-sensitive tasks. Confidence: High

- Flexible tactile sensing systems face practical challenges in integration, calibration and durability. Confidence: High

- TACTO is an open-source simulator for vision-based tactile sensors aimed at high-throughput tactile rendering for learning. Confidence: High

- Amazon’s “Vulcan” is reported as a warehouse robot using tactile sensing to retrieve items from shelves. Confidence: Medium (journalistic report; technical details not independently verified here)

- A Scientific Reports review reports haptic feedback in robot-assisted surgery reduced forces in studied tasks, with variability. Confidence: High

- Sensory feedback for prostheses is described in reviews as improving control and embodiment, with multiple delivery methods. Confidence: Medium (effects can vary by study and method)

- ISO/TS 15066 specifies safety requirements for collaborative industrial robot systems and work environments. Confidence: High

- ISO-related literature reviews discuss how ISO 15066 is used and where gaps remain. Confidence: High

- “Haptics with Input” demonstrates using linear resonant actuators for sensing touch and pressure via back electromotive force. Confidence: High

- Latency affects haptic and teleoperation performance and is studied in surveys and experiments. Confidence: High