Every secure transaction you make today, every encrypted email you send, every digital signature you trust, relies on mathematical problems that are extraordinarily difficult for today's computers to solve. Breaking the encryption that protects a typical bank transfer would take a classical supercomputer thousands of years. But a sufficiently powerful quantum computer could do it in hours.

This is not a distant, theoretical concern. Adversaries are already harvesting encrypted data today, stockpiling it for future decryption when quantum computers become powerful enough. Intelligence agencies call this "harvest now, decrypt later." Your organisation's sensitive communications, customer data, intellectual property, and financial records intercepted today could be exposed tomorrow, even if they remain encrypted by current standards.

For UK organisations, particularly those in finance, healthcare, government, and critical infrastructure, the quantum threat is not about whether quantum computers will break today's encryption, but when. The consensus among experts places this "Q-Day" somewhere between 2030 and 2040, with estimates concentrated around 2033-2035. The US National Security Agency requires exclusively post-quantum cryptography from suppliers as early as 2030, with full transition by 2035.

The message is clear: organisations must begin their transition to quantum-resistant cryptography now. This article explains what quantum computing actually is, cuts through the hype, and provides a practical roadmap for preparation.

What Quantum Computing Is (and Is Not)

Quantum computing is a fundamentally different approach to computation that exploits the strange behaviours of matter at the subatomic scale. Unlike classical computers, which process information as binary bits (0s and 1s), quantum computers use quantum bits, or qubits, which can exist in multiple states simultaneously.

A quantum computer is not simply a faster version of today's computers. It cannot run Windows, browse the web, or play games better than your laptop. Instead, quantum computers excel at a specific class of problems where they can explore vast numbers of possibilities in parallel. These include simulating molecular interactions for drug discovery, optimising complex logistics networks, and, crucially, breaking certain types of encryption.

Classical computers store and process data sequentially, using billions of transistors that are either on (1) or off (0). Their power increases linearly as you add more bits. Quantum computers, by contrast, can process information in ways that are fundamentally inaccessible to classical machines. When you add qubits to a quantum system, the computational power increases exponentially. Two qubits can represent four states simultaneously, three qubits can represent eight states, and 100 qubits can represent more states than there are atoms in the observable universe.

However, quantum computers are not general-purpose machines. They require specialised algorithms designed to take advantage of quantum phenomena. For most everyday computing tasks, classical computers will remain superior for the foreseeable future. Quantum computers are best understood as specialised co-processors that will work alongside classical systems to solve specific, intractable problems.

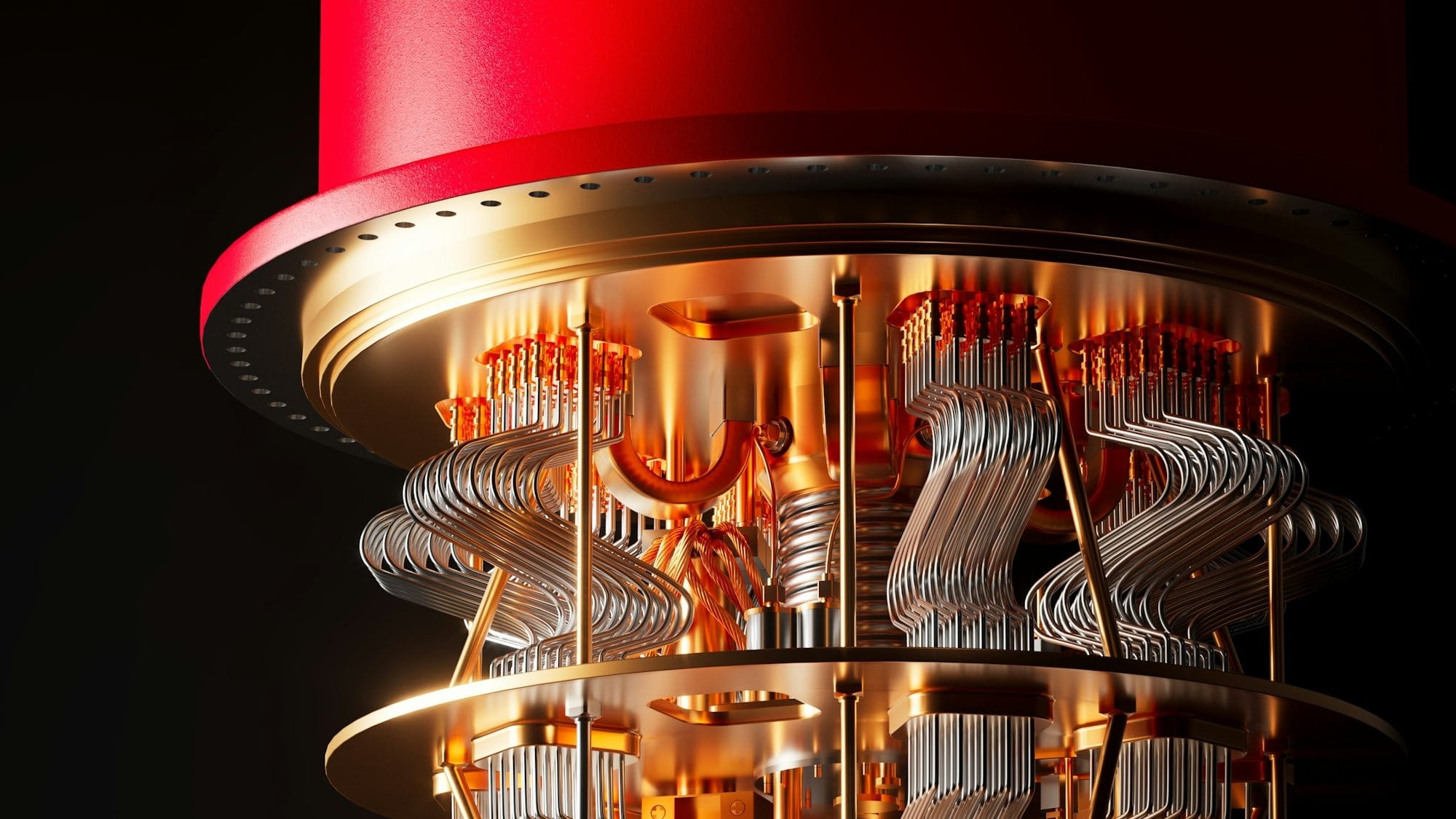

The quantum computers being built today are still in their infancy. IBM, Google, Microsoft, and others are racing to build systems with hundreds or thousands of qubits, but these machines are extraordinarily fragile, requiring temperatures near absolute zero and isolation from all environmental interference. Despite these limitations, progress is accelerating rapidly.

The Core Concepts: Qubits, Superposition, and Entanglement

To understand why quantum computers pose such a threat to current encryption, you need to grasp three fundamental quantum phenomena: qubits, superposition, and entanglement.

Qubits: The Building Blocks

A qubit is the quantum equivalent of a classical bit, but with a crucial difference. While a classical bit must be either 0 or 1, a qubit can exist in a superposition of both states simultaneously. This is not the same as being "halfway between" 0 and 1, nor is it simply that we do not know which state it is in. The qubit genuinely exists in both states at once until it is measured.

Qubits can be implemented in various ways. Superconducting qubits use tiny circuits cooled to near absolute zero, trapped ion qubits use individual atoms held in place by electromagnetic fields, and photonic qubits use particles of light. Each approach has trade-offs in terms of stability, speed, and scalability.

When you measure a qubit, its superposition collapses into either 0 or 1. The probability of each outcome depends on the qubit's quantum state before measurement. This probabilistic nature is fundamental to quantum mechanics and cannot be eliminated.

Superposition: Parallel Possibilities

Superposition allows quantum computers to explore many possible solutions simultaneously. Imagine searching for a specific page in a vast library. A classical computer would check each book sequentially. A quantum computer in superposition can, in a sense, check multiple books at once.

This does not mean quantum computers simply try all possibilities and pick the right answer. Instead, quantum algorithms are designed to amplify the probability of correct answers whilst cancelling out incorrect ones through a process called interference. The quantum state evolves like a wave, with peaks representing likely solutions and troughs representing unlikely ones.

However, superposition is extraordinarily fragile. Any interaction with the environment, even a stray photon or vibration, can cause the quantum state to collapse prematurely, a process called decoherence. Maintaining superposition requires isolating qubits at temperatures colder than outer space and shielding them from all external interference.

Entanglement: Spooky Connections

Entanglement is a quantum phenomenon where two or more qubits become correlated in such a way that the state of one instantly influences the state of the others, regardless of the distance between them. Einstein famously called this "spooky action at a distance" and was deeply uncomfortable with it, but experiments have repeatedly confirmed that entanglement is real.

When qubits are entangled, measuring one qubit immediately determines the state of the others. This does not allow faster-than-light communication (information still cannot travel faster than light), but it does enable quantum computers to process information in ways that are impossible for classical systems.

Entanglement is essential for quantum computing power. It allows quantum algorithms to create and manipulate complex correlations between qubits, enabling them to solve certain problems exponentially faster than classical computers. Without entanglement, a quantum computer would be little more than a probabilistic classical machine.

Why Cryptography Is the Real Story

Whilst quantum computing promises breakthroughs in drug discovery, materials science, and optimisation, the most immediate and consequential impact will be on cryptography. This is not speculation. It is mathematical certainty.

The Threat: Shor's Algorithm

In 1994, mathematician Peter Shor discovered an algorithm that allows a quantum computer to factor large numbers exponentially faster than any known classical algorithm. This was a watershed moment. Factoring large numbers is the mathematical foundation of RSA encryption, which secures everything from online banking to government communications.

RSA encryption relies on the fact that multiplying two large prime numbers is easy, but factoring the result back into those primes is extraordinarily difficult. A classical computer would need thousands of years to factor a 2048-bit RSA key. Shor's algorithm running on a sufficiently powerful quantum computer could do it in hours or days.

The same vulnerability affects other widely used cryptographic systems. Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC), Diffie-Hellman key exchange, and Digital Signature Algorithm (DSA) all rely on mathematical problems that quantum computers can solve efficiently. Once a cryptanalytically relevant quantum computer (CRQC) exists, these systems will be effectively broken.

Importantly, symmetric encryption like AES and hash functions like SHA-256 are less vulnerable. A quantum algorithm called Grover's algorithm can speed up brute-force attacks, but only by squaring the effort, effectively halving the security bit strength. AES-256 would still provide approximately 128-bit security against quantum attacks, which remains acceptable. The crisis is specifically with public-key (asymmetric) cryptography.

The Timeline: Closer Than You Think

When will quantum computers become powerful enough to break current encryption? Most experts place "Q-Day" between 2030 and 2040, with a concentration of estimates around 2033-2035. However, recent advances have shortened these projections.

In 2025, research by Craig Gidney showed that breaking RSA-2048 requires fewer than one million superconducting qubits, down from earlier estimates of 20 million. This brings Q-Day approximately seven years closer, assuming qubit counts continue to double every 18 months.

Google's 2024 announcement of its Willow quantum chip demonstrated the first scalable implementation of error correction, a major milestone. Whilst Willow is far from breaking encryption, it proves that the engineering challenges are surmountable.

Harvest Now, Decrypt Later

Even if Q-Day is a decade away, the threat exists today. Adversaries are already intercepting and storing encrypted data with the intention of decrypting it once quantum computers become available. This "harvest now, decrypt later" strategy is particularly concerning for data that must remain confidential for years or decades, such as medical records, financial transactions, state secrets, and intellectual property.

US cybersecurity authorities, including CISA, NSA, and NIST, have jointly warned that cyber threat actors could be targeting data today for future decryption. For organisations in healthcare, finance, and government, this means that sensitive data transmitted today is already at risk.

Post-Quantum Cryptography: What It Means

Post-quantum cryptography (PQC) refers to cryptographic algorithms that are secure against both classical and quantum computers. Unlike quantum key distribution, which requires specialised quantum hardware, PQC algorithms can run on today's classical computers whilst remaining resistant to quantum attacks.

NIST Standards: The Foundation

In August 2024, the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) published the first three post-quantum cryptography standards: FIPS 203, 204, and 205. These standards specify quantum-resistant algorithms for key encapsulation and digital signatures, providing a clear path for organisations to implement PQC.

FIPS 203 specifies ML-KEM (Module-Lattice-Based Key Encapsulation Mechanism), based on the CRYSTALS-Kyber algorithm. This is the primary method for securely exchanging encryption keys in a post-quantum world.

FIPS 204 specifies ML-DSA (Module-Lattice-Based Digital Signature Algorithm), based on CRYSTALS-Dilithium, for creating and verifying digital signatures that remain secure against quantum attacks.

FIPS 205 specifies SLH-DSA (Stateless Hash-Based Digital Signature Algorithm), based on SPHINCS+, as a backup signature method with different mathematical foundations.

NIST is continuing to evaluate additional algorithms, including the code-based HQC encryption algorithm announced in 2025. The goal is to provide multiple options with different security assumptions, ensuring that if one approach is compromised, alternatives remain secure.

Government and Industry Timelines

The US National Security Agency's Commercial National Security Algorithm Suite 2.0 (CNSA 2.0) mandates transition to post-quantum algorithms by 2033 for National Security Systems, with some high-priority cases required by 2030. The UK government is targeting one million error-free quantum operations by 2028. Australia plans completion by 2030, whilst the EU expects transitions between 2030 and 2035.

NIST's timeline, driven by White House directives, targets deprecation of quantum-vulnerable algorithms by 2030 and complete removal by 2035. This gives organisations a 10-year window to complete their migration, which may sound generous but is extremely tight given the complexity of cryptographic infrastructure.

Major technology companies are already implementing PQC. Google's Willow project and partnerships between IBM and Thales demonstrate that market leaders are taking the transition seriously. Apple has begun migrating iMessage to post-quantum algorithms, and Cloudflare reports that approximately 50% of global internet traffic is now protected against quantum-era decryption attacks.

Myths Versus Reality

Myth: Quantum computers will make all encryption obsolete.

Reality: Only public-key cryptography is vulnerable. Symmetric encryption like AES-256 and hash functions like SHA-512 remain secure with appropriate key sizes. The transition to post-quantum cryptography addresses the specific vulnerability of RSA, ECC, and similar algorithms.

Myth: Quantum computers will be exponentially faster at everything.

Reality: Quantum computers excel at specific problems like factoring, database search, and simulation. For most everyday computing tasks, including word processing, web browsing, and video streaming, classical computers will remain superior. Quantum computers are specialised co-processors, not replacements for classical systems.

Myth: We can wait until quantum computers are more mature before acting.

Reality: The "harvest now, decrypt later" threat means that data intercepted today is already at risk. Additionally, many organisations have technology refresh cycles of 10-20 years. Systems deployed today with only classical encryption could become security liabilities within their operational lifetime.

Myth: Post-quantum cryptography is unproven and risky.

Reality: NIST's standardisation process involved years of rigorous evaluation by cryptographers worldwide. The selected algorithms have been extensively analysed and are considered secure against both classical and quantum attacks. Waiting for "more proof" simply delays necessary preparation.

Myth: Small organisations do not need to worry about quantum threats.

Reality: Any organisation that handles sensitive data, whether customer information, financial records, or intellectual property, faces quantum risk. Regulatory requirements in finance and healthcare will likely mandate post-quantum cryptography, making compliance essential regardless of organisation size.

Prepare Now: A Checklist for Small and Mid-Sized Organisations

Transitioning to post-quantum cryptography is a complex, multi-year programme. However, organisations can begin taking concrete steps today to prepare.

1. Inventory Your Cryptographic Assets

Identify where cryptography is used throughout your organisation. This includes TLS certificates for websites, VPN connections, digital signatures, encrypted databases, secure email, and authentication systems. Document which algorithms are in use (RSA, ECC, etc.) and their key sizes.

Pay particular attention to long-lived data. Medical records, financial transactions, and intellectual property that must remain confidential for decades are highest priority.

2. Assess Your Supply Chain

Cryptographic security depends not only on your own systems but also on suppliers, cloud providers, and software vendors. Contact key suppliers to understand their post-quantum roadmaps. Include PQC requirements in procurement processes for new systems.

3. Prioritise Key Exchange First

Post-quantum key exchange using ML-KEM should be your first priority. This prevents "harvest now, decrypt later" attacks. Many systems can adopt hybrid approaches that use both classical and post-quantum key exchange, providing protection without breaking compatibility.

4. Plan for Certificate Transitions

Digital signatures and certificates are more complex to migrate than key exchange. Post-quantum signatures like ML-DSA produce larger signatures (approximately 15KB additional data per TLS handshake), which can cause performance issues on slow networks. Begin testing post-quantum certificates in non-production environments.

5. Implement Crypto-Agility

Design systems with "crypto-agility", the ability to swap cryptographic algorithms without major architectural changes. This is essential because post-quantum algorithms are relatively new, and vulnerabilities may be discovered that require rapid updates.

6. Budget and Resource Allocation

Transitioning to post-quantum cryptography requires investment in new hardware, software updates, staff training, and potentially external consultants. Begin allocating budget now. History shows that cryptographic migrations take 3-4 years to complete.

7. Stay Informed

The post-quantum landscape is evolving rapidly. Subscribe to updates from NIST's Post-Quantum Cryptography project, follow guidance from the UK's National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), and engage with industry groups working on PQC implementation.

8. Test and Validate

Before deploying post-quantum cryptography in production, conduct thorough testing. Verify compatibility with existing systems, measure performance impacts, and ensure that hybrid approaches (using both classical and post-quantum algorithms) function correctly.

The Challenges and Timeline: What to Expect

Whilst the path to post-quantum security is clear, significant challenges remain.

Error Correction: The Bottleneck

Current quantum computers are "noisy", meaning they make frequent errors. Quantum error correction (QEC) is essential for building reliable, large-scale quantum computers, but it requires massive overhead. A single logical qubit (one that can perform reliable computations) might require 1,000 to 10,000 physical qubits, depending on error rates.

Recent breakthroughs, including Google's demonstration of below-threshold error correction and IBM's work on high-threshold codes, show that progress is accelerating. However, scaling to the hundreds of thousands or millions of qubits needed to break RSA-2048 remains a formidable engineering challenge.

Hardware Limitations

Quantum computers require extreme conditions: temperatures near absolute zero, isolation from vibration and electromagnetic interference, and precise control of individual qubits. Scaling up whilst maintaining these conditions is extraordinarily difficult.

Different qubit technologies face different challenges. Superconducting qubits are fast but noisy and require complex refrigeration. Trapped ion qubits are high-quality but slow and difficult to scale beyond a few dozen qubits. Neutral atom qubits offer promising scalability but are still maturing.

The Uncertainty Range

Given these challenges, predictions for Q-Day vary widely. Conservative estimates place it in the 2040s or beyond. Optimistic (or pessimistic, depending on your perspective) estimates suggest the early 2030s. The consensus centres on 2033-2035, but this is not a hard deadline. Breakthroughs in error correction, qubit quality, or algorithmic efficiency could accelerate the timeline significantly.

What is certain is that waiting until a CRQC is publicly announced will be far too late. By that point, any data intercepted in the preceding years will be vulnerable. Organisations must act on the assumption that Q-Day could arrive sooner than expected.

Conclusion: Act Now, Not Later

Quantum computing represents both extraordinary promise and significant peril. The same technology that could revolutionise drug discovery and materials science will also render much of today's cryptography obsolete. For organisations, the question is not whether to prepare for post-quantum cryptography, but how quickly they can complete the transition.

The good news is that the path forward is clear. NIST has published robust standards, governments have set timelines, and major technology companies are leading the way. Post-quantum cryptography is not a speculative technology. It is available today and can be implemented on existing classical hardware.

The bad news is that time is short. With Q-Day potentially arriving in the early 2030s and cryptographic migrations typically requiring 3-4 years, organisations that delay action risk being caught unprepared. The "harvest now, decrypt later" threat means that sensitive data is already at risk.

Related reading

- The economics of AI: why inference costs matter more than flashy demos

- AI translation and speech tools: accuracy, bias, and when to trust them

For UK organisations, particularly those in regulated industries like finance and healthcare, the imperative is clear: begin your post-quantum transition now. Inventory your cryptographic assets, engage with suppliers, prioritise key exchange, and allocate resources. The quantum era is not a distant future. It is arriving faster than most people realise, and the organisations that prepare today will be the ones that remain secure tomorrow.