In a lab that smells faintly of warm plastic and disinfectant, a researcher peers at something that looks like a clear postage stamp. Inside, a thin channel carries a steady trickle of fluid past living human cells. On a nearby incubator shelf sit “mini-organs” in tiny droplets of gel, each a lumpy, self-organising cluster with ambitions far larger than its size. None of this is science fiction. It is the slow reinvention of toxicology and disease modelling, driven by a blunt fact: too many drugs that look safe and effective in animals disappoint, or harm, in people.

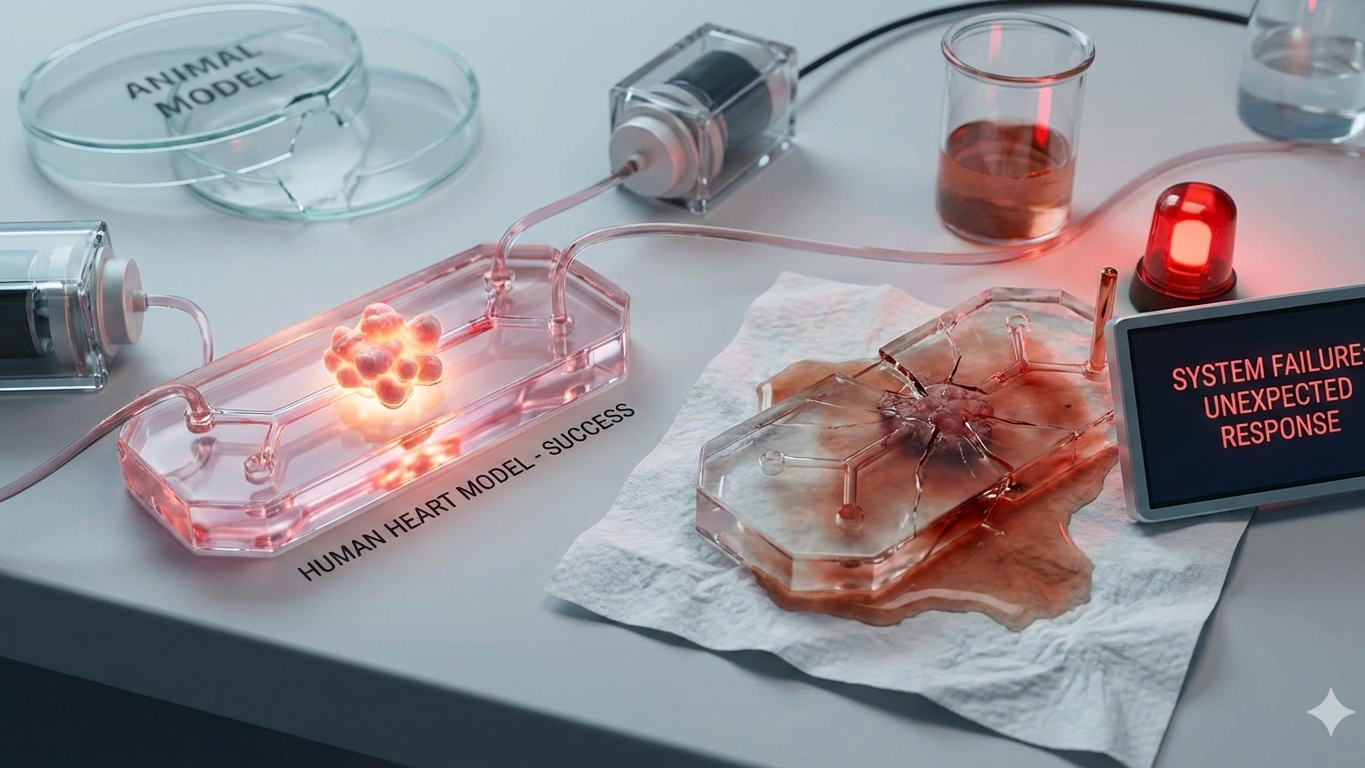

The new toolkit is two related technologies. Organoids are three-dimensional (3D) cell cultures that self-organise into tissue-like structures. Organ-on-chip systems, also called microphysiological systems (MPS), are micro-engineered devices that culture cells under controlled flows and forces to mimic aspects of organ function. Increasingly, researchers combine them into organoid-on-chip platforms, hoping to get the best of both worlds.

The promise is seductive: less reliance on animals, better prediction of human toxicity, and even a form of “patient-in-a-dish” medicine where treatments are tested on your cells before you take them. The reality is more interesting and more awkward.

Mini-organs, big claims: what organoids are

Organoids are grown from adult stem cells taken from tissues, or from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) that can be coaxed to become many cell types. Given the right cues, they self-organise into structures that resemble aspects of an organ, such as intestinal crypts, liver-like tissue, or brain-region models. Reviews emphasise their power for modelling human genetics and aspects of tissue architecture, while also stressing that “organoid” covers a wide range of systems with variable fidelity.

The crucial point is what they are not. Most organoids do not reproduce a full organ with its blood supply, immune system, innervation, and long-term maturation. They model slices of biology, sometimes beautifully, sometimes misleadingly.

How you grow a gut in gel

The recipe varies by tissue, but the logic is similar.

Cells are embedded in a scaffold, often a gel that mimics the extracellular matrix, then fed a cocktail of growth factors that nudges them down a developmental path. Over days to weeks, they proliferate and self-organise. Some organoids can be expanded and banked, creating living libraries of patient-derived material for research and, potentially, clinical decision support. Cancer organoids, for example, can preserve features of tumour heterogeneity and are being explored for drug testing and biomarker discovery.

It is clever. It is also fragile. Small changes in media, matrix, handling, and timing can alter cell composition and behaviour. That variability is why standards and reporting guidance are becoming a central theme, not an afterthought.

Chips, flows and forces: what “organ-on-chip” adds

Organ-on-chip systems aim to recreate the physical context that organoids often lack. They use microfluidic channels to control flow, gradients, and mechanical cues, for example, stretch in lung models or shear stress in vascular models. The FDA and others describe MPS as promising tools that combine microsystems engineering and cell biology to capture key biological processes and disease states.

This matters because cells behave differently when they feel the right forces, receive nutrients in a more physiological way, and interact across barriers such as epithelium and endothelium. Chips can also make it easier to sample outputs, image responses, and connect multiple tissues to study organ-organ interactions.

The field’s long-term dream is a modular human body-on-a-chip. The nearer-term reality is more modest: better models for specific questions, with clearer performance boundaries.

What these models can, and cannot, replicate

Organoids and chips can be excellent at modelling:

- Human genetics, including patient-specific mutations.

- Cell-cell interactions within a tissue-like architecture.

- Barrier functions, such as gut lining or airway epithelium.

- Certain infectious processes, where the pathogen’s interaction with human tissue is the key unknown.

They struggle with:

- Full-body physiology, including endocrine feedback and complex pharmacokinetics.

- Immune complexity, unless immune components are deliberately added.

- Long-term maturation, especially for tissues like brain, where development unfolds over long timeframes.

- Reproducibility at scale, when the same “organoid type” means slightly different things in different labs.

A useful mental model is to treat them as high-resolution zoom lenses, not replacement bodies. They can show details animals may miss, but they can also miss what whole organisms reveal.

Where they outperform animals, and where they fail

There are good reasons regulators and funders are paying attention. In April 2025, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published a roadmap to reduce animal testing in some preclinical safety studies by adopting scientifically validated new approach methodologies (NAMs), including organ-on-chip systems and organoid assays. The UK has also signalled direction of travel in its strategy to support non-animal methods.

Organoids and chips can outperform animals when:

- The question hinges on human-specific biology, such as certain drug metabolism pathways, transporters, or infection dynamics;

- Animal models are a poor match for a human disease mechanism;

- The need is for mechanistic clarity, not statistical correlation.

They fail when:

- Toxicity depends on whole-body interactions, long-term exposure, or complex immune responses;

- The model lacks crucial cell types or physical context;

- The readout is oversold as “predictive” without robust validation.

Validation is the unglamorous axis here. Toxicology is conservative for a reason. A test is useful only if it performs reliably, across labs, across compounds, against known outcomes.

Drug toxicity: the slow reinvention of preclinical safety

Toxicology is where organ-on-chip systems have the most immediate narrative pull, partly because late-stage toxicity failures are expensive and sometimes catastrophic. The NIH tissue chip programme has explicitly supported development of tissue chips for safety and efficacy testing and has built translational centres to improve adoption.

The best-case scenario is not a single chip that replaces an animal study. It is a portfolio of human-relevant assays that identify specific hazards earlier, reduce animal use where appropriate, and sharpen decisions about which candidates deserve costly clinical trials. The FDA’s roadmap frames this as a stepwise shift, not an overnight abolition.

Rare disease: when “patient-in-a-dish” is not just marketing

Rare diseases often suffer from a bleak arithmetic: too few patients for large trials, too many unknowns about mechanism. Organoids can help because they preserve patient genetics and can be tested repeatedly.

Cystic fibrosis has become a flagship example. Patient-derived organoid swelling assays have been investigated as functional tools that correlate with clinical response to CFTR modulators, providing a route to predict benefit in some contexts.

This is not a universal template. It works best when a disease has a clear functional readout and the organoid model captures the relevant biology. Many rare diseases are less tidy.

Oncology response testing: hope, and a hard boundary

Patient-derived tumour organoids can preserve elements of a tumour’s heterogeneity and are widely explored as platforms for drug testing and biomarker discovery.

The boundary is that tumours live in ecosystems. Immune cells, stromal cells, blood vessels, and extracellular matrix all shape drug response. Organoid systems can be augmented with co-cultures and microfluidics, but the more realism you add, the harder standardisation becomes. The question is not whether organoids can help oncology; they clearly can. The question is when they will meaningfully change routine treatment selection, beyond niche settings.

Infectious disease: modelling human tissues under human rules

Infectious disease is a sweet spot for human tissue models because pathogens exploit species-specific features. Reviews describe organoids as valuable systems for studying infections and supporting drug and vaccine development, including for viruses such as SARS-CoV-2.

Organ-on-chip platforms have also been used to model respiratory infections and host responses in vitro. A well-cited airway-on-a-chip study showed the technology can model viral infection and immune cell recruitment, illustrating how chips can add dynamic features to tissue models.

These models do not replace epidemiology or clinical trials. They can, however, sharpen mechanistic understanding and provide more human-relevant testbeds than many animal systems.

Standards, reproducibility, and the boring details that decide everything

If this field has a villain, it is not the mouse; it is variance.

Organoid research has faced scrutiny over fidelity and reproducibility, particularly in brain organoids, where quantitative analysis and detailed reporting are repeatedly flagged as essential. More broadly, standards for organoid production and quality assessment have been proposed to improve trustworthiness and comparability.

For organ-on-chip, standardisation is also becoming formalised. A CEN-CENELEC roadmap published in 2024 discusses the need for validation and assessment for regulatory toxicology, reflecting that these systems sit awkwardly across device-like and assay-like worlds.

In toxicology, good practice frameworks matter. OECD guidance on Good In Vitro Method Practices (GIVIMP) exists precisely to support reliability, documentation, and appropriate interpretation for in vitro methods.

The blunt message is that the future of organoids and chips will be decided by standard operating procedures, reference materials, inter-lab ring trials, and performance metrics, not conference demos.

Whose cells, whose consent: equity and biobanks

“Human-relevant” raises an immediate question: which humans?

Cell sources for organoids and iPSC-derived models often come from biobanks and clinical samples. Ethical issues include informed consent, privacy, governance of genetic data, and whether donors understand long-term and secondary uses. The Nuffield Council on Bioethics has highlighted consent and data protection concerns in organoid research, including the fact that organoids share DNA with donors.

There are also equity questions about representation. If biobanks over-represent certain ancestries or socioeconomic groups, then “patient-in-a-dish” risks becoming “some patients in a dish”. Debates about biospecimen consent and participant engagement are active, especially as iPSC lines and organoids become infrastructure, not one-off experiments.

Access is another layer. If these systems help personalise treatment decisions, who pays, and who benefits, especially in publicly funded health systems already under strain.

Five things that could go wrong

Five things that could go wrong

- The model is not the disease: an organoid captures a tissue fragment but misses immune, vascular, or hormonal context, producing confident nonsense.

- Batch effects swamp biology: differences in media, matrix, handling, or imaging pipelines drive results more than the drug.

- Validation never catches up: impressive prototypes proliferate, but few platforms undergo rigorous, multi-site validation for regulatory use.

- The dataset is unrepresentative: biobanks reflect convenience, not population diversity, narrowing applicability and widening inequities.

- Hype outruns scope: “patient-in-a-dish” is sold as a clinical oracle, then under-delivers, damaging trust and funding for genuinely useful niches.

What “patient-in-a-dish” can realistically deliver

The most realistic version of patient-in-a-dish is not universal prediction. It is decision support in defined scenarios.

It can work when:

- The disease mechanism is tractable in vitro;

- The organoid readout correlates with meaningful clinical endpoints;

- The turnaround time fits clinical workflow;

- And the test is validated, not merely plausible.

It is likely to disappoint when it is used as a stand-in for whole-body pharmacology or long-term safety, or when it is expected to choose between treatments whose differences depend on immune effects and systemic exposure.

The future is incremental, which is exactly the point

Organoids and organ-on-chip systems are not replacing animals wholesale tomorrow. They are, however, changing the centre of gravity of preclinical science, from what is convenient to what is human-relevant and measurable. Regulators are signalling openness to NAMs, and funders in the UK and US are investing in infrastructure to accelerate non-animal approaches.

The best way to understand this shift is to see it as a slow upgrade of the evidence pipeline. Better human tissue models will not abolish uncertainty. They can, if handled with discipline, reduce the most avoidable kinds of surprise.

In toxicology, fewer surprises is a revolution that arrives quietly. That is probably what success looks like.