Novo Nordisk's terrible week reveals the brutal economics of the obesity drug gold rush

A 20% share price collapse, the first sales decline forecast in years, and rock-bottom pricing for its new Wegovy pill signal the end of easy profits in weight-loss treatments. The question now is whether anyone can make money in this market

Nordisk's catastrophic week offers a stark lesson in how quickly dominance can turn to desperation in pharmaceutical markets. The Danish company that pioneered the obesity drug revolution now finds itself slashing prices, warning of revenue declines, and watching its market value evaporate at a pace that has stunned even seasoned biotech investors.

Wednesday's 16 to 20% share price collapse in Copenhagen, triggered by guidance forecasting a 5 to 13% drop in 2026 sales and operating profit, was remarkable not just for its severity but for what it revealed about the new economics of obesity treatment. Despite beating fourth-quarter earnings expectations and posting 10% sales growth for 2025, investors ignored the positive news entirely. The message was clear: the past no longer matters when the future looks this bleak.

The numbers tell a brutal story. Novo has shed $450 billion in market value since early 2024, according to Bloomberg, with shares down 68% from their highs. The company that was once poised to become Europe's most valuable has seen an entire year's gains wiped out in a single trading session. For context, 2025 now ranks as Novo's worst year on record.

Price collapse changes everything

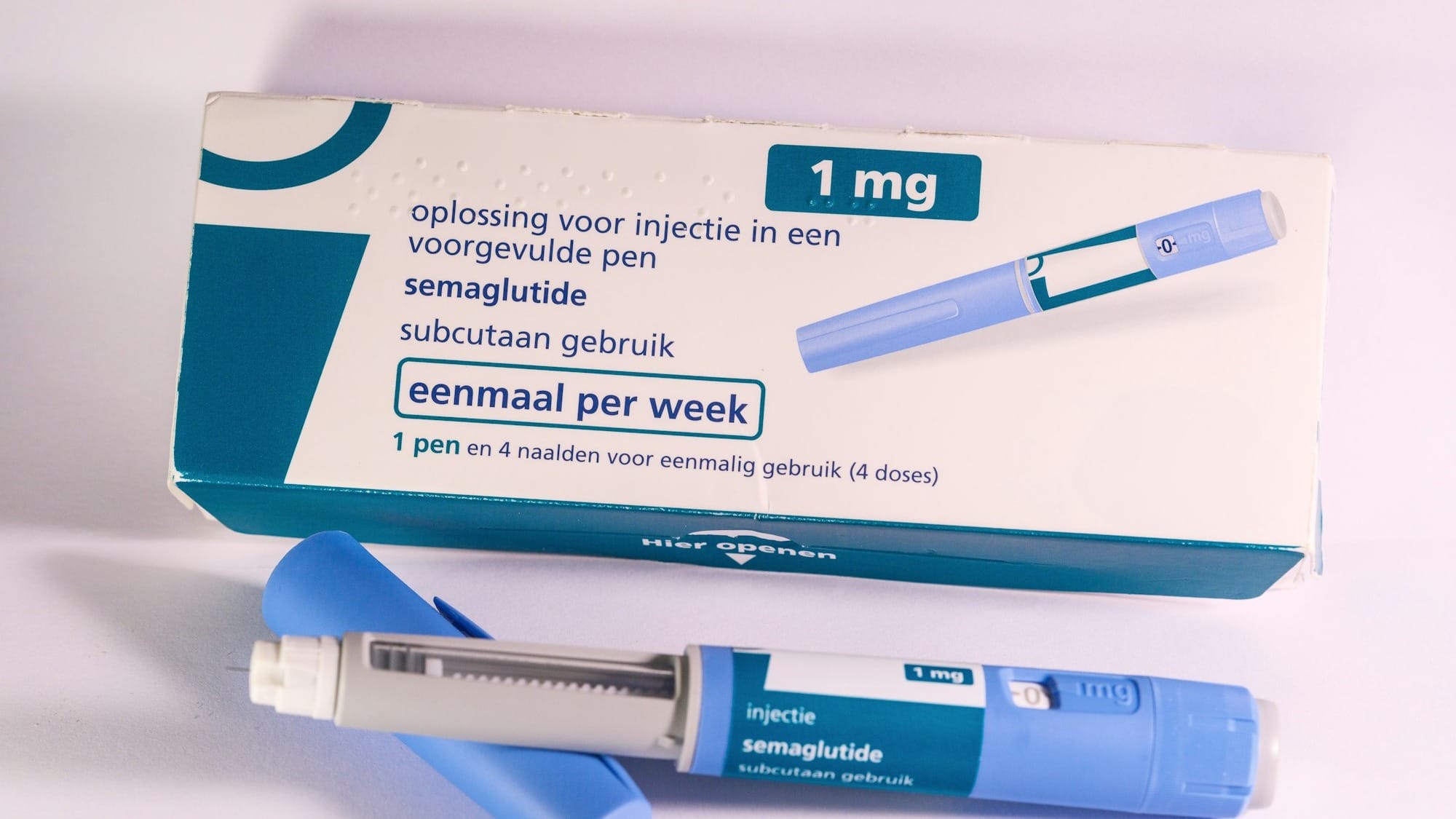

The most revealing development came not from the guidance itself but from the pricing strategy that necessitated it. Novo launched its oral Wegovy pill last month at $149 per month for starter doses, roughly one-ninth the price of its injectable version at $1,349, according to CNBC. This is not a modest adjustment or a promotional discount. This is a wholesale repricing of what obesity treatment costs in America.

The implications extend far beyond Novo's balance sheet. If the company that invented and dominated this market cannot sustain premium pricing, what hope do competitors have? Eli Lilly, which has been aggressively pursuing market share with its own obesity treatments, must now be reassessing its own pricing assumptions. The entire sector was built on the premise that obesity drugs could command prices similar to other chronic disease treatments. That premise now looks shaky.

CEO Mike Doustdar's warning to CNBC that "people should expect that it goes down before it comes back up" was refreshingly candid, but it raises uncomfortable questions about whether revenues will come back up at all. Novo is framing these cuts as a strategic investment to expand the patient base, betting that volume can compensate for lower unit prices. That works in consumer goods markets with low marginal costs. It is far less proven in pharmaceuticals, where manufacturing, distribution, and regulatory compliance remain expensive regardless of price.

Patent expiries accelerate the commoditisation

The timing could hardly be worse. Just as Novo slashes prices in its most important market, it is losing patent protection on semaglutide in Canada, Brazil, and China this year. The generic manufacturers preparing to enter those markets will not be aiming for $149 per month. They will be targeting prices that reflect the true cost of production, which industry observers estimate to be a fraction of even Novo's discounted rates.

This creates a vicious dynamic. As generics flood international markets, they will establish new price anchors that make Novo's current pricing look expensive by comparison. Patients and insurers will inevitably question why they should pay substantially more for a branded product when the active ingredient is identical. Novo will need a compelling answer beyond brand recognition, and so far it has not articulated one.

The weekend retreat by Hims & Hers, which halted sales of its $49 compounded Wegovy copycat following FDA scrutiny, offered Novo a temporary reprieve. But the episode demonstrated the appetite for low-cost alternatives and the ease with which nimble competitors can undercut established players. Novo may have won this particular battle through regulatory pressure, but the war over pricing is far from over.

When good science meets bad economics

Perhaps the saddest aspect of Novo's week was the market's complete indifference to genuinely positive clinical news. The Phase three REIMAGINE 2 trial results for CagriSema, the company's next-generation obesity drug, showed superior blood sugar control and weight loss compared to current semaglutide formulations. In any normal environment, such results would fuel optimism about Novo's pipeline and future growth.

Instead, investors shrugged. The message: scientific excellence no longer guarantees commercial success in this market. CagriSema might be more effective than Wegovy, but if Novo cannot charge premium prices for Wegovy, why should anyone expect it to command them for CagriSema?

This disconnect between clinical performance and financial performance represents a fundamental shift in how obesity drugs are valued. The market has concluded that efficacy alone is insufficient to justify high prices when competition is fierce and payers are resistant. Novo's next-generation products will need to demonstrate not just better outcomes but dramatically better outcomes that justify meaningfully higher prices. That is a far more challenging proposition.

Trump administration's clunking fist hand

Lurking behind all of this is the TrumpRx programme, which has clearly spooked Novo into pre-emptive price cuts. The administration's push for lower drug prices has created an environment where pharmaceutical companies feel compelled to slash prices before being forced to do so through regulation or political pressure.

This dynamic is particularly potent in obesity drugs, where the patient population is enormous and the budgetary impact on insurers and government programmes is substantial. Unlike rare disease treatments, where small patient populations and lack of alternatives provide pricing leverage, obesity drugs face the twin pressures of large-scale budget impact and growing competition.

Novo's decision to cut prices dramatically suggests the company believes political pressure would only intensify if it maintained premium pricing. Whether that calculation proves correct depends on how aggressively the Trump administration pursues drug pricing reform and whether it treats pre-emptive cuts as sufficient or merely a starting point for further reductions.

What comes next

The leadership change at Novo's US business, with Jamie Miller replacing David Moore effective this week, adds another variable to an already uncertain situation. Miller inherits responsibility for executing a strategy of aggressive pricing and volume growth in a market that has lost faith in that strategy. His success or failure will likely determine whether Novo can stabilise revenues or faces further declines beyond 2026.

For the broader pharmaceutical industry, Novo's week serves as a warning about the fragility of blockbuster drug economics in an era of political pressure, generic competition, and payer resistance. The obesity drug market was supposed to be different—a rare opportunity to address a massive unmet medical need with treatments that genuinely worked. Instead, it is rapidly becoming commoditised, with prices converging toward levels that make it difficult for anyone to earn substantial returns.

The question now is not whether Novo can return to its former heights. It is whether the obesity drug market can support the kind of innovation and investment that created these treatments in the first place. If the answer is no, patients and society will ultimately pay the price through reduced innovation in future treatments. Novo's terrible week may prove to be just the beginning of a broader reckoning for the pharmaceutical industry.