Antibiotic resistance has a way of turning medicine backwards. A routine infection becomes a long hospital stay. A standard operation becomes riskier because the safety net of effective antibiotics frays.

The basic biology is simple. Bacteria evolve. The more we expose them to antibiotics, especially when we do not need to, the more likely resistant strains are to win. WHO estimates bacterial AMR was directly responsible for 1.27mn deaths in 2019 and contributed to 4.95mn deaths.

The economics are stranger. The world needs new antibiotics, but also needs to preserve them. That is a market designed to disappoint investors. The O’Neill review, commissioned from the UK, called this a market failure and argued for new incentives that reward value rather than sales. The UK’s experiment is a subscription-style payment model that pays companies a fixed annual fee for access to an antibiotic based on assessed value, not on how much is used.

So what does the “new antibiotics hunt” actually look like in 2026? Less like a single breakthrough, more like a crowded toolbox.

What is real today

The most reliable AMR tools are also the least glamorous: infection prevention, surveillance, and better use of existing antibiotics.

In England, UKHSA’s ESPAUR programme tracks antimicrobial use and resistance. Its recent lay summary reports that between 2019 and 2024 the number of antibiotic-resistant infections increased from 18,103 to 20,484, an increase of 13.1%. NICE stewardship guidance sets out systems and processes designed to change prescribing practice and slow resistance. “Start smart then focus” provides a practical hospital framework: prescribe promptly when needed, then review, refine or stop.

These steps do not sound like innovation. They are. They keep antibiotics working long enough for new approaches to arrive.

What is promising but early

Phage therapy, precision with logistical pain

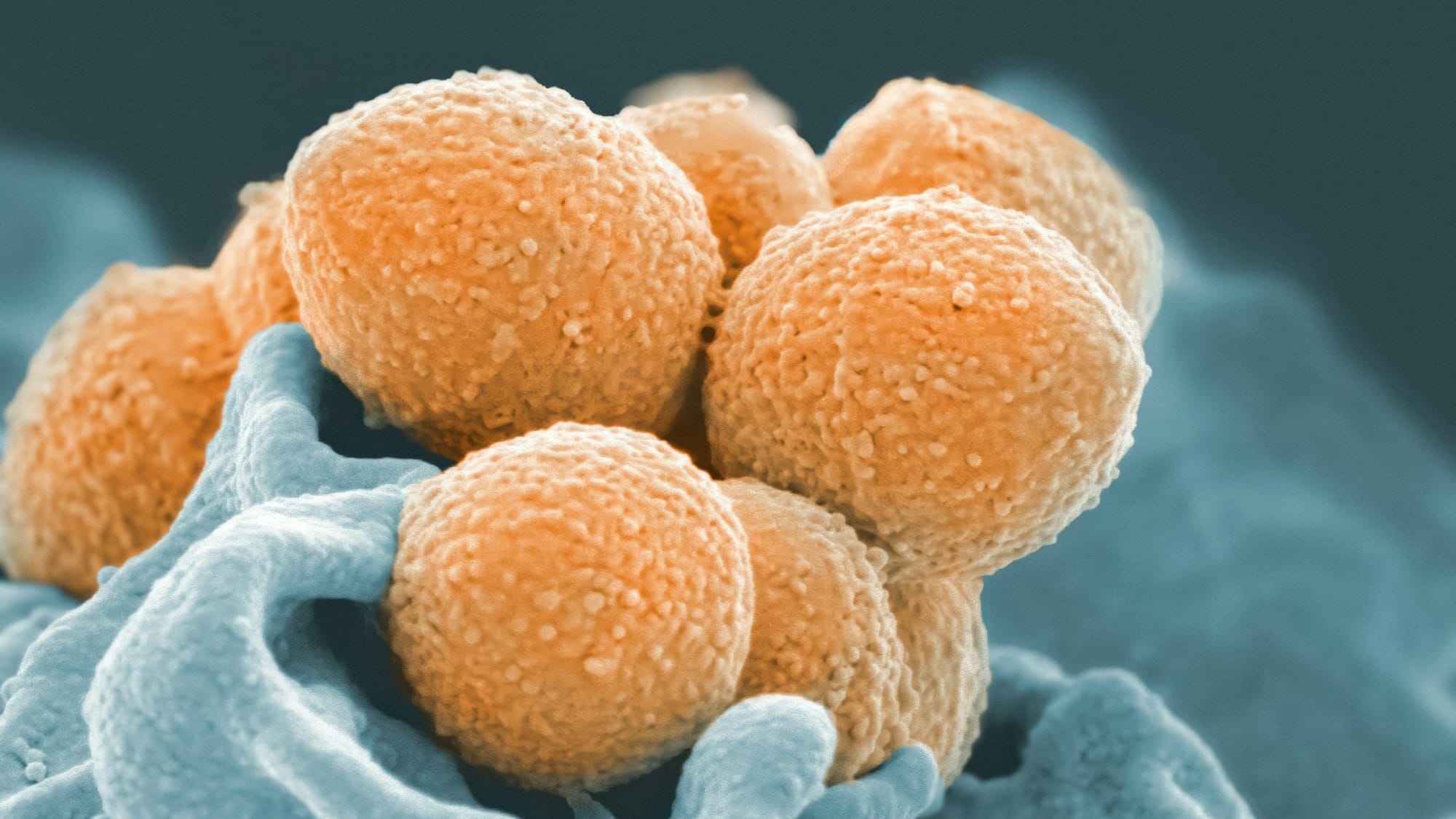

Bacteriophages are viruses that infect bacteria. Unlike antibiotics, which can hit multiple species, phages are often highly specific. That makes them attractive for targeted killing, and less likely to wipe out bystander bacteria in the gut. It also makes them hard to deploy quickly.

For many infections, you would need to identify the culprit bacterium, match it to phages that kill it, and deliver the treatment in time. To broaden coverage and reduce bacterial escape, teams use phage cocktails, mixtures of phages designed to cover multiple strains.

The clinical evidence is growing, but uneven. A Nature Microbiology commentary calling for the field notes reported clinical improvements across many cases while also pointing to the need for stronger evidence and clearer pathways. A 2024 review on phage therapy in respiratory infections illustrates the problem: the biology is compelling, but delivery, matching and standardised trials are hard.

Phages also face an awkward truth. Resistance evolves here too. The advantage is that phages can, in principle, be updated and reselected. The disadvantage is that regulators and manufacturers prefer stable products.

Bacteriocins, bacterial weapons as medicines

Bacteriocins are antimicrobial molecules made by bacteria to kill other bacteria. Some can be potent and targeted. Reviews have argued they deserve serious attention as antibiotic alternatives, and later comprehensive reviews set out the landscape and constraints.

The familiar barriers follow. Many bacteriocins are peptides, and peptides can be unstable in the body. Dosing and delivery matter. Manufacturing and regulatory standardisation matter.

One interesting trend is to stop thinking of bacteriocins as pills and start thinking of them as outputs from engineered microbes. A 2024 Nature Communications paper describes a bacteriocin secretion platform using engineered bacteria, a step towards live biotherapeutic delivery rather than purified drug. That approach could solve some delivery problems and create new safety and governance problems.

Antimicrobial peptides, broad promise, narrow safety window

Antimicrobial peptides, or AMPs, are part of nature’s own antimicrobial toolkit. Many work by disrupting membranes. That can make them fast-acting, but also raises toxicity risks if they harm human cells.

A 2023 review highlights why clinical development is difficult, focusing on instability and toxicity as recurring obstacles. A 2025 review surveys the AMP development landscape and argues progress is real but constrained by practical issues like delivery and manufacturability.

AI is starting to enter here too, not as an oracle but as a way to explore peptide design space more efficiently. A 2025 Nature Microbiology paper reports a generative AI approach to discover new AMPs against multidrug-resistant bacteria, largely at a preclinical stage.

Microbiome approaches, change the habitat

The microbiome angle treats infection and resistance partly as an ecosystem problem. Antibiotics can clear pathogens, but also disrupt protective communities, creating openings for opportunists.

The strongest established example is faecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent C. difficile infection. NICE has published guidance on FMT for recurrent C. difficile, and UK clinical literature stresses the importance of donor screening and controlled delivery. Outside that, microbiome approaches are moving towards defined microbial products and engineered bacteria, but the evidence is narrower and harder to generalise.

AI-designed drugs, faster discovery, same slow development

AI can help identify candidate antibiotics by screening chemical libraries and prioritising molecules likely to work. The poster child is halicin, identified through deep learning and then validated experimentally, including in animal models.

The part that headlines often omit is what AI does not compress: toxicity studies, dosing, pharmacokinetics, manufacturing, and clinical trials. A 2025 perspective in npj Antimicrobials and Resistance emphasises both the promise of AI and the need for careful validation and translation.

How not to get misled by headlines

A useful rule is to ask what stage the claim is at.

- In vitro means “in a dish”. Many candidates die later.

- In vivo animal models are a step closer, but still not a human result.

- Clinical evidence means controlled trials with outcomes that matter.

Second, watch for scope creep. A therapy that works for a narrow, well-defined infection can still be valuable, but it is not “the end of antibiotics”.

Third, follow the bottlenecks. For phages and live biotherapeutics, manufacturing and standardisation are as important as clever biology. For peptides, safety and stability are the gatekeepers. For AI drugs, the gatekeepers are the same as ever: chemistry, safety, and trials.

Finally, keep an eye on incentives. A brilliant antibiotic that nobody can afford to develop is not a solution. That is why the UK’s subscription model matters, even if it is not science fiction.

Fact-check list (claims, sources, confidence)

- WHO estimates bacterial AMR was directly responsible for 1.27mn deaths in 2019 and contributed to 4.95mn deaths. High

- WHO GLASS 2025 report analyses antibiotic resistance trends using millions of lab-confirmed cases reported by more than 100 countries. High

- UKHSA ESPAUR lay summary reports antibiotic-resistant infections in England increased from 18,103 in 2019 to 20,484 in 2024, a 13.1% rise. High

- NICE NG15 guideline aims to optimise antimicrobial use to slow emergence of resistance. High

- UK “Start smart then focus” toolkit supports hospital antimicrobial stewardship and aligns with NICE stewardship guidance. High

- O’Neill review describes antibiotic development incentives as a market failure and argues for delinked pull incentives. High

- NICE and NHS England subscription model pays a fixed annual fee for antimicrobials based on value rather than volumes used. High

- Phage therapy is being advocated for and has reported case outcomes, but evidence quality and standardisation remain challenges. Medium-High (evidence base varies by indication and setting)

- A 2024 review discusses phage therapy potential for lower respiratory tract infections and the need for alternative approaches due to AMR. High

- Bacteriocins are antimicrobial molecules produced by bacteria and have been proposed as alternatives to traditional antibiotics. High

- A 2024 Nature Communications paper reports a modular bacteriocin secretion platform using engineered bacteria. High

- Antimicrobial peptide development faces recurring challenges including toxicity and metabolic instability. High

- A 2025 Nature Microbiology paper reports a generative AI approach for discovery of AMPs against multidrug-resistant bacteria. High

- NICE has guidance on faecal microbiota transplant for recurrent C. difficile infection. High

- Stokes et al (2020) reports a deep learning approach that identified halicin and validated antibacterial activity experimentally, including in murine models. High

- A 2025 perspective discusses how AI can support AMR efforts including drug discovery, while emphasising validation. High