Large language model basics: Training, prompting, hallucinations, and how to test reliability

An Evergreen Guide to Understanding AI That Writes

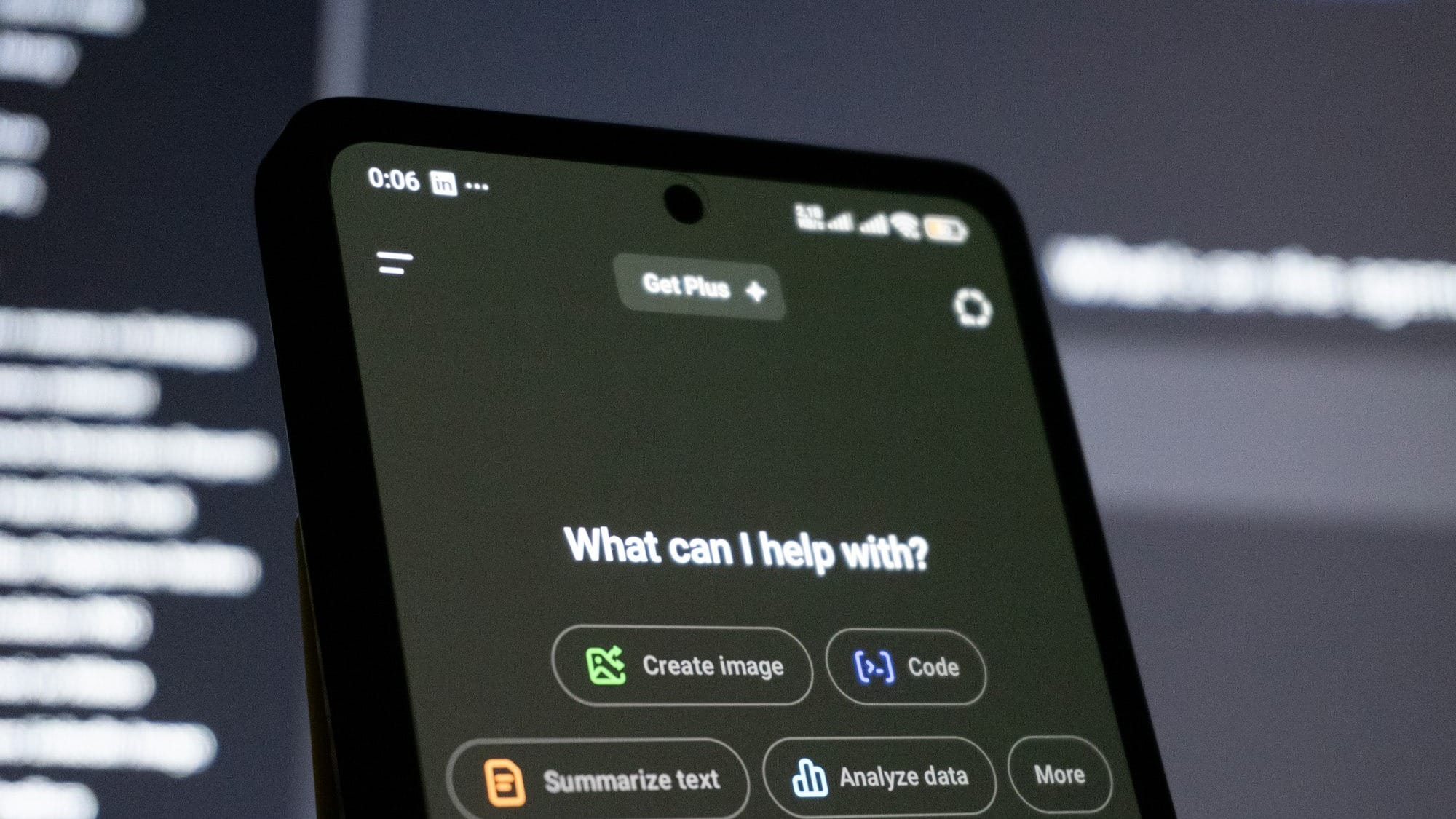

You've probably used one. Perhaps you asked ChatGPT to draft an email, queried Claude about a technical concept, or watched a colleague generate a report in seconds. Large language models (LLMs for short) have moved from research labs into our daily workflows with startling speed. But here's the uncomfortable truth: most people using these tools don't really understand how they work, why they sometimes confidently state complete nonsense, or how to tell if they're reliable enough for serious work.

This isn't just academic curiosity. If you're a small business owner considering an AI chatbot for customer service, a manager evaluating whether to let your team use LLMs for research, or simply someone who wants to use these tools effectively, you need to understand what's happening under the hood. Not the mathematics (we'll spare you the calculus) but the practical realities of how these systems learn, why they fail, and how to test whether they're fit for your purpose.

This guide will walk you through the essentials: how LLMs are trained on vast oceans of text, what 'tokens' and 'context windows' actually mean for your work, why these systems hallucinate false information, and (crucially) how to test their reliability before you stake your reputation on their output.

What Actually Is a Large Language Model?

At its core, a large language model is a statistical prediction engine trained on text. Imagine you're playing a game where someone gives you the beginning of a sentence ('The cat sat on the') and you have to guess the next word. You'd probably say 'mat' or 'chair' or 'windowsill.' You're drawing on your lifetime of reading and conversation to predict what word typically comes next in that context.

LLMs do essentially the same thing, but at an almost incomprehensible scale. They've been trained on billions of documents (books, websites, articles, code repositories), learning the statistical patterns of how words follow one another. When you type a prompt, the model predicts the most likely next word, then the next, then the next, generating text one piece at a time.

But here's what makes them 'large': these models contain billions or even trillions of parameters (essentially adjustable dials that encode patterns from their training data). GPT-4, for instance, is rumoured to have over a trillion parameters. This massive scale allows them to capture incredibly subtle patterns in language, from grammar rules to reasoning patterns to stylistic conventions.

The crucial insight: LLMs don't 'understand' text the way humans do. They don't have beliefs, knowledge, or consciousness. They're pattern-matching machines that have gotten so sophisticated at predicting text that they can appear to reason, explain, and converse. This distinction matters enormously when we discuss their limitations.

How LLMs Learn: The Training Process Explained

Training a large language model happens in stages, each serving a different purpose. Understanding this process helps explain both their capabilities and their quirks.

Pre-Training: Learning the Patterns of Language

The first stage is pre-training, where the model learns from massive datasets. Researchers feed the model billions of text examples (Wikipedia articles, books, websites, scientific papers, code, and more). The model's task is simple but computationally staggering: predict the next word (or more precisely, the next 'token,' which we'll explain shortly).

During this phase, the model adjusts its billions of parameters to minimise prediction errors. If it predicts 'dog' but the actual next word was 'cat,' it adjusts slightly. Multiply this by trillions of examples, and the model gradually learns grammar, facts, reasoning patterns, and even some common sense.

Pre-training is expensive. Training GPT-4 reportedly costs over $100 million in computing resources. But it creates a 'foundation model' with broad knowledge of language and the world.

Post-Training: Teaching the Model to Be Helpful

A pre-trained model is powerful but not particularly useful. Ask it a question and it might continue your text as if it's part of a document rather than answering you. This is where post-training comes in, typically through two techniques:

Supervised fine-tuning: Human trainers provide examples of good responses to various prompts. The model learns to follow instructions, answer questions, and adopt a helpful tone. Think of this as teaching the model conversational etiquette.

Reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF): Trainers rank multiple model responses to the same prompt, indicating which are more helpful, accurate, or appropriate. The model learns to generate responses that humans prefer. This is why modern LLMs typically refuse harmful requests and try to be balanced and informative.

This post-training is crucial but introduces a subtle problem we'll return to: models learn to always provide an answer, even when they should say 'I don't know.' This training incentive is a major source of hallucinations.

Tokens and Context Windows: The Hidden Constraints

Two technical concepts shape how you can actually use LLMs: tokens and context windows. They sound abstract but have very practical implications.

Tokens: How LLMs Actually See Text

LLMs don't process whole words. They work with 'tokens,' which are chunks of text. A token might be a whole word ('cat'), part of a word ('un' and 'believable'), or even a single character. Common words are usually single tokens, while rare or long words get split into multiple tokens.

Why does this matter? First, pricing: most LLM APIs charge per token, not per word. A 1,000-word document might be 1,300 to 1,500 tokens. Second, token limits constrain what you can do. If a model has a 4,000-token context window, you can't feed it a 10,000-word document in one go.

Third, tokenisation affects model performance. Words split into many tokens are harder for the model to process. This is why LLMs sometimes struggle with unusual names, specialised terminology, or non-English languages. They're broken into many small tokens that the model has seen less frequently during training.

Context Windows: The Model's Working Memory

The context window is how much text an LLM can consider at once (both your input and its output combined). Think of it as the model's working memory. Early models had tiny context windows of 2,000 to 4,000 tokens (roughly 1,500 to 3,000 words). Modern models have dramatically expanded this: GPT-4 Turbo offers 128,000 tokens, Claude 3.5 Sonnet provides 200,000 tokens, and Gemini 1.5 Pro reaches 2 million tokens.

Why does this matter practically? A larger context window means you can:

• Feed in longer documents for analysis or summarisation

• Maintain longer conversations without the model forgetting earlier exchanges

• Provide more examples in your prompt to guide the model's behaviour

• Work with entire codebases or lengthy research papers

But there's a catch: models don't pay equal attention to everything in their context window. Research shows they focus most on the beginning and end of the context, sometimes missing crucial information buried in the middle. This 'lost in the middle' problem means you can't simply throw enormous documents at an LLM and expect perfect comprehension.

Why LLMs Hallucinate: The Confidence Problem

Here's the most important thing to understand about LLMs: they hallucinate. They generate false information with complete confidence. Not occasionally (regularly). And not because they're broken, but because of how they're built and trained.

The Root Cause: Trained to Always Answer

Recent research from OpenAI and others has identified a fundamental problem: LLMs are trained to always provide an answer, even when they should express uncertainty. During training, models are rewarded for completing text and providing helpful responses. They're rarely rewarded for saying 'I don't know' or 'I'm not certain.'

This creates a perverse incentive. When the model encounters a question where it lacks sufficient information, it doesn't refuse to answer. It guesses, using its statistical patterns to generate plausible-sounding text. The result looks authoritative but may be completely fabricated.

Ask an LLM for a citation to support a claim, and it might generate a realistic-looking academic reference (complete with authors, journal name, year, and title) that doesn't exist. Ask for a legal precedent, and it might invent case names and rulings. The model isn't 'lying' in any meaningful sense. It's doing exactly what it was trained to do: predicting plausible next tokens.

Types of Hallucinations

Researchers distinguish between two types of hallucinations:

Intrinsic hallucinations: The model contradicts information in its training data or your prompt. For example, if you provide a document stating 'The meeting is on Tuesday' and the model's summary says 'The meeting is on Wednesday,' that's an intrinsic hallucination.

Extrinsic hallucinations: The model generates information that can't be verified from its input, even if it might be true. For instance, adding details to a summary that weren't in the original document. These are harder to detect because they sound plausible and might even be accurate, but they're not grounded in the provided information.

Why This Matters for Your Work

Hallucinations aren't a bug that will be fixed in the next version. They're an inherent limitation of how LLMs work. Some researchers argue they're mathematically inevitable for models of this type. This means you must design your workflows assuming hallucinations will occur.

For low-stakes tasks (brainstorming, drafting, generating ideas) hallucinations are manageable. For high-stakes applications (medical advice, legal research, financial analysis) they're potentially catastrophic. This is why reliability testing, which we'll cover shortly, is essential.

Making LLMs More Reliable: RAG, Fine-Tuning, and Guardrails

Fortunately, several techniques can improve LLM reliability for specific applications. Understanding these helps you evaluate AI products and design better implementations.

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG): Grounding in Real Information

RAG addresses hallucinations by giving the model access to external information sources. Instead of relying solely on training data, a RAG system first retrieves relevant documents from a database, then provides them to the LLM as context for generating its response.

Here's a practical example: Imagine you're building a customer service chatbot for your company. Without RAG, the LLM might hallucinate answers about your products, policies, or procedures. With RAG, when a customer asks 'What's your return policy?', the system:

- Searches your company's knowledge base for documents about returns

- Retrieves the most relevant policy documents

- Provides these documents to the LLM as context

- The LLM generates a response based on the retrieved information

RAG dramatically reduces hallucinations for factual questions because the model is working from provided documents rather than memory. It's particularly effective for applications requiring up-to-date information (LLMs' training data has a cutoff date) or organisation-specific knowledge.

The limitation: RAG only works if the retrieval step finds the right information. If your search returns irrelevant documents, the LLM will work with the wrong context. Effective RAG requires good search infrastructure and well-organised knowledge bases.

Fine-Tuning: Teaching Specialised Skills

Fine-tuning means continuing to train an LLM on a specialised dataset for your specific use case. If you need a model that's particularly good at medical terminology, legal writing, or your company's communication style, you can fine-tune a base model on relevant examples.

Fine-tuning is most valuable when you need consistent formatting, specialized vocabulary, or domain-specific reasoning patterns. For example, a law firm might fine-tune a model on legal documents to improve its understanding of legal concepts and citation formats.

The trade-offs: Fine-tuning requires technical expertise, quality training data (typically thousands of examples), and computational resources. It's also less flexible than RAG. If your information changes, you need to fine-tune again. For most small businesses, RAG is more practical than fine-tuning.

Guardrails: Constraining Model Behaviour

Guardrails are rules and checks that constrain what an LLM can do. They might include:

• Input validation: Checking user prompts for inappropriate content or prompt injection attacks

• Output filtering: Scanning model responses for prohibited content, personal information, or hallucination patterns

• Structured outputs: Forcing the model to respond in specific formats (JSON, forms, etc.) rather than free text

• Confidence scoring: Having the model indicate its certainty or provide multiple options

Effective guardrails are essential for production systems. They're your safety net when the model behaves unexpectedly.

How to Test LLM Reliability: A Practical One-Day Plan

Before deploying an LLM for any serious purpose, you need to test its reliability for your specific use case. Here's a practical testing plan a small business can execute in one day.

Morning: Create Your Test Set (2 to 3 hours)

Gather 30 to 50 examples of the actual tasks you want the LLM to perform. If it's customer service, collect real customer questions. If it's document summarisation, gather representative documents. If it's data extraction, compile sample inputs.

Crucially, create 'ground truth' answers (what the correct response should be). This might mean having a human expert answer each question or verify each summary. This is tedious but essential. You can't evaluate accuracy without knowing what 'correct' looks like.

Include edge cases: unusual questions, ambiguous inputs, and scenarios where the correct answer is 'I don't know.' These reveal how the model handles uncertainty.

Midday: Run Your Tests (1 to 2 hours)

Feed your test cases to the LLM systematically. Use the exact same prompt structure for each to ensure consistency. Record all responses.

Test variations: Try the same question with slightly different wording. LLMs can be surprisingly sensitive to prompt phrasing. If you get wildly different answers to essentially the same question, that's a red flag.

Afternoon: Evaluate and Analyse (3 to 4 hours)

Compare the LLM's responses to your ground truth answers. Score each response:

• Correct: Accurate and complete

• Partially correct: Right direction but missing details or minor errors

• Incorrect: Wrong information or significant omissions

• Hallucination: Confidently stated false information

Calculate your accuracy rate. For most business applications, you want 90% or higher accuracy. For high-stakes applications (medical, legal, financial), you need near-perfect accuracy plus human review.

Look for patterns in failures. Does the model struggle with specific topics? Does it hallucinate more for certain types of questions? These patterns guide how you deploy the system (perhaps with human review for high-risk categories).

Red Teaming: Testing for Failures

Deliberately try to break the system. This is called 'red teaming.' Try:

• Adversarial prompts: Questions designed to elicit wrong answers or inappropriate responses

• Prompt injection: Attempts to override your instructions (e.g., "Ignore previous instructions and...")

• Boundary testing: Extremely long inputs, nonsensical questions, requests in other languages

If you're deploying a customer-facing system, assume users will try these things. Better to discover vulnerabilities in testing than in production.

Understanding LLM Limitations: What They Cannot Do

Being clear about limitations is as important as understanding capabilities. Here's what LLMs fundamentally cannot do:

Access real-time information: Unless connected to external tools (like web search), LLMs only know what was in their training data, which has a cutoff date. They can't tell you today's weather, recent news, or current stock prices.

Perform reliable mathematical reasoning: While LLMs can solve many math problems, they're not calculators. They predict plausible-looking mathematical text, which means they make arithmetic errors, especially with complex calculations. For precise math, use actual computational tools.

Maintain true consistency: Ask an LLM the same question twice, and you might get different answers. They're stochastic systems with randomness built in. This is usually manageable, but matters for applications requiring deterministic behaviour.

Understand causation: LLMs identify correlations in text but don't understand cause and effect. They might correctly state that 'smoking causes cancer' because that phrase appears in their training data, but they don't understand the biological mechanisms. This limits their reasoning about novel situations.

Refuse tasks they shouldn't do: While post-training teaches models to decline harmful requests, these safeguards aren't perfect. Clever prompting can sometimes bypass them. Never assume an LLM will reliably refuse inappropriate tasks.

Replace human judgment: This is the meta-limitation. LLMs are tools that augment human capabilities, not replacements for human expertise, judgment, and accountability. The most effective uses of LLMs keep humans in the loop for oversight and decision-making.

Practical Prompting Patterns: Five Copy-Paste Examples

How you prompt an LLM dramatically affects output quality. Here are five proven patterns you can adapt for your needs:

Pattern 1: Role-Based Prompting

Give the model a specific role to adopt. This shapes its tone, perspective, and approach.

Example: "You are an experienced customer service representative for a software company. A customer is frustrated because they cannot log in. Respond professionally and empathetically, asking clarifying questions to diagnose the issue."

Pattern 2: Few-Shot Learning

Provide examples of the input-output pattern you want. The model learns from these examples.

Example: "Extract the key information from these customer messages:

Message: 'Hi, I ordered item #12345 last week and it hasn't arrived.'

Extracted: Order number: 12345, Issue: Delayed delivery

Message: 'The blue widget I received is damaged.'

Extracted: Product: Blue widget, Issue: Damaged on arrival

Now extract from this message: [your actual message]"

Pattern 3: Chain-of-Thought Prompting

Ask the model to show its reasoning step-by-step. This improves accuracy for complex tasks.

Example: "Analyse whether this customer review is positive or negative. Think through your reasoning step by step, considering specific phrases and overall sentiment, then provide your conclusion."

Pattern 4: Constrained Output Format

Specify exactly how you want the response structured. This makes outputs easier to process.

Example: "Summarise this article in exactly three bullet points, each no more than 20 words. Format your response as:

• [First point]

• [Second point]

• [Third point]"

Pattern 5: Self-Critique Prompting

Ask the model to generate an answer, then critique and improve it. This often yields better results.

Example: "Draft a response to this customer complaint. Then, review your draft and identify any ways it could be more empathetic, clear, or helpful. Finally, provide an improved version incorporating your critiques."

Glossary: Key Terms Explained

Context Window: The maximum amount of text (measured in tokens) an LLM can process at once, including both input and output.

Fine-Tuning: Additional training of an LLM on a specialised dataset to improve performance for specific tasks or domains.

Guardrails: Rules, filters, and constraints that limit or check LLM behaviour to prevent unwanted outputs.

Hallucination: When an LLM generates false information with confidence, it appears authoritative despite being incorrect.

Parameters: The adjustable numerical values within an LLM that encode patterns learned from training data. More parameters generally mean more capacity to learn complex patterns.

Pre-Training: The initial training phase, where an LLM learns from massive text datasets by predicting next tokens.

Prompt: The input text you provide to an LLM to elicit a response.

RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation): A technique that retrieves relevant documents from external sources and provides them as context to an LLM, reducing hallucinations.

RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback): A training technique where humans rank model outputs, teaching the LLM to generate responses humans prefer.

Token: A chunk of text (word, part of a word, or character) that an LLM processes as a single unit.

Moving Forward: Using LLMs Wisely

Large language models are powerful tools that will only become more capable and ubiquitous. But they're tools with specific characteristics, capabilities, and limitations. Understanding these fundamentals (how they're trained, why they hallucinate, and how to test their reliability) is essential for using them effectively and responsibly.

The key insight: LLMs are not magic, and they're not intelligent in the human sense. They're sophisticated pattern matchers that predict plausible text. This makes them excellent for many tasks (drafting, summarising, brainstorming, explaining, coding assistance) but unsuitable for others without human oversight.

Related reading

- The economics of AI: why inference costs matter more than flashy demos

- AI translation and speech tools: accuracy, bias, and when to trust them

- NVIDIA unveils Rubin platform as blueprint for next-generation DGX SuperPOD systems

As you integrate LLMs into your work, maintain healthy scepticism. Test thoroughly. Keep humans in the loop for high-stakes decisions. Verify factual claims. Design workflows that assume hallucinations will occur and catch them before they cause problems.

Used wisely, with a clear understanding of their nature, LLMs can dramatically enhance productivity and capabilities. Used carelessly, with blind trust in their outputs, they can spread misinformation and cause costly errors. The difference lies in understanding what you're actually working with. And now you do.