While the narrative of the last two years has focused on the brilliance of large language models and the agility of software, the industry’s future is now dictated by a much more prosaic reality: the availability of high-voltage transformers, water permits, and stable electrical grids. Infrastructure, not ingenuity, is now the primary limiting factor in the global AI arms race.

How the infrastructure stack fits together

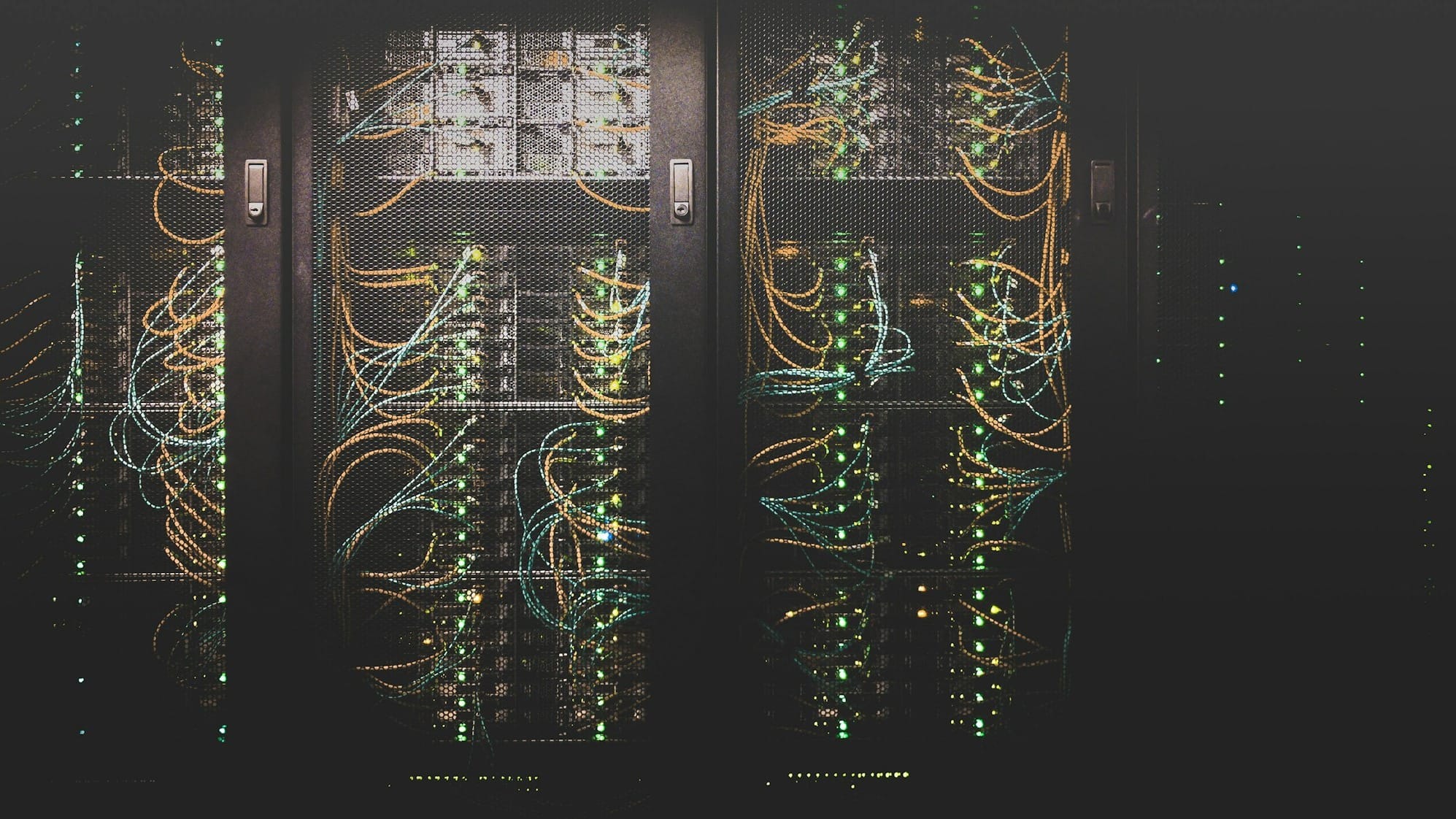

To the casual observer, a data centre is simply a warehouse full of computers. To an engineer, it is a complex thermodynamic system designed to move heat away from silicon as fast as possible. The AI infrastructure stack is divided into three distinct categories, each serving a different purpose.

First are the hyperscale facilities. These are the gargantuan campuses owned by titans such as Microsoft, Amazon, and Google. They are purpose-built for massive compute tasks, such as training a new foundation model. A single hyperscale site can draw as much as 100 megawatts (MW) of power—enough to supply 80,000 households—and as the industry moves into 2026, planned "gigawatt-scale" clusters are beginning to appear on blueprints.

Second are colocation (or "colo") centres. These are the "hotels" of the data world, where multiple companies lease space, power, and cooling. They provide the flexibility for smaller firms to run AI workloads without building their own warehouses. Finally, there is the edge. These are small, modular units placed close to end-users—perhaps in a city basement or at a 5G base station. They are essential for "inference", the process where an AI gives you an answer in real-time without the lag of sending data to a distant hyperscale hub.

The cooling crisis: beyond air and fans

As AI chips become more powerful, they also become significantly hotter. A traditional server rack might draw 10 kilowatts (kW) of power, but a rack filled with the latest Nvidia Blackwell or Rubin chips can draw over 100kW. This has rendered traditional air cooling—essentially giant air conditioning units—obsolete for high-end AI.

The industry is rapidly shifting towards liquid cooling. This involves direct-to-chip systems where coolant is pumped through a cold plate sitting directly on the processor. Even more extreme is immersion cooling, where the entire server is submerged in a bath of non-conductive, synthetic oil. These technologies are more efficient, but they introduce new risks: a single leak in a liquid-cooled manifold can result in millions of pounds of hardware being written off in seconds.

Bottlenecks: the search for power and water

The search for suitable sites is becoming increasingly desperate. In the UK, the data centre market is the largest in Europe, with a capacity of approximately 1.6 gigawatts (GW) in 2024. However, preliminary analysis for the government suggests this needs to quadruple by 2030 to meet demand.

The primary bottleneck is the grid. In west London, housing developers have famously been told they may have to wait years for new connections because data centres have "hogged" the available capacity. This has forced a shift in strategy. Rather than waiting for National Grid upgrades, operators are increasingly looking at "behind-the-meter" solutions, such as building their own small modular nuclear reactors (SMRs) or massive on-site battery arrays.

Water has emerged as the second great constraint. A mid-sized data centre can consume as much water as a town of 10,000 people to keep its cooling towers running. In water-stressed regions, this is leading to political friction. Google reported using over 5 billion gallons of water across its data centres in 2023, and as the boom continues, local authorities are increasingly demanding "closed-loop" systems that recycle every drop, even if they are more expensive to run.

Myth-busting: the AI data centre

Myth: Data centres are huge job creators for local areas. Fact: While construction requires thousands of workers, a finished data centre is highly automated. A £10 billion campus might only employ 400 permanent staff, many of whom are security and maintenance personnel.

Myth: The "cloud" is invisible and weightless. Fact: The cloud is a heavy industrial asset. By the end of 2026, global data centre electricity consumption is forecast to surpass 1,000 terawatt-hours (TWh), roughly the total electricity consumption of Japan.

Myth: AI will eventually become so efficient it won't need these huge buildings. Fact: While software is becoming more efficient, the scale of ambition is growing faster. We are using efficiency gains to build larger models, not smaller data centres.

Environmental trade-offs: the green dilemma

The data centre boom presents a profound environmental paradox. On one hand, tech giants are the world’s largest corporate buyers of renewable energy, single-handedly funding the construction of new wind and solar farms. On the other hand, the "baseload" requirement of a data centre—it must run 24 hours a day, regardless of whether the wind is blowing—often forces grids to keep gas or coal plants running longer than planned.

Furthermore, there is the "embedded carbon" in the concrete and steel required to build these facilities, and the "water tension" created in local communities. As the industry matures, we are likely to see a move towards "waste heat recovery", where the heat generated by AI chips is piped into local district heating systems to warm homes and greenhouses, turning a waste product into a community asset.

How to read a data centre announcement

When a company announces a new "AI-ready" facility, look past the headline investment figure and check these four indicators:

- Power Density: Is it rated for 50kW per rack or more? If it’s lower, it isn't a true AI facility; it’s a traditional data centre with a marketing rebrand.

- PUE (Power Usage Effectiveness): This is the ratio of total energy used to energy delivered to the computers. A score of 1.0 is perfect. Anything over 1.3 is considered outdated for 2026 standards.

- Water Source: Does it use "potable" (drinking) water or "grey" (recycled) water? Public opposition is much higher for facilities using the former.

- Grid Connection Status: Has the power been "allocated" or just "requested"? Many projects are announced before a firm connection date is secured, leading to years of delays.

The outlook: what is structural versus what will change

Related reading

- The economics of AI: why inference costs matter more than flashy demos

- AI translation and speech tools: accuracy, bias, and when to trust them

- NVIDIA unveils Rubin platform as blueprint for next-generation DGX SuperPOD systems

Some constraints are temporary. The current shortage of electrical transformers and specialised power engineers is a supply chain "hiccup" that will likely ease by 2027. However, the fundamental laws of physics and thermodynamics are structural. We cannot continue to air-cool 100kW racks, and we cannot build gigawatt-scale campuses without fundamentally redesigning how national grids operate.

As the industry moves towards the end of the decade, the winners will not be the ones with the best algorithms, but the ones who secured the land, the power, and the cooling infrastructure first. In the AI arms race, the "hidden" constraints have finally become the most visible part of the story.